Foreword by Dr. Karen B. DeSalvo, MD, MPH, MSc

As content writers and developers of consumer digital health information tools, you are faced with the difficult task of imagining what your end users will find understandable and actionable. There are a number of strategies that can help (e.g., use cases, personas, and user requirements) to make your tools more user friendly. But these strategies cannot always close the experience gap that exists between writers and developers and their end users. That is why user research is so important. It can provide insights into how users interact with and understand digital health information. This guide provides actionable steps for creating more accessible consumer-centric digital tools that have the potential to ease the burden of navigating complex digital health information.

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has developed this 2nd edition of Health Literacy Online: A Guide to Simplifying the User Experience, an updated version of the 2010 guide, to help bridge this gap. Derived from extensive research with more than 800 users, this updated guide offers practical insights into a full range of users’ navigation experiences, particularly those who struggle with reading and health literacy, and can be used to help create intuitive, easy-to-use digital health information tools.

This 2nd edition of Health Literacy Online is aligned with the President’s Digital Government Strategy, which calls for new and better ways to deliver digital information and services anytime, anywhere, and on any device. Since its conception, Health Literacy Online has informed the responsively designed healthfinder.gov, an award-winning website developed by ODPHP that reflects the commitment of HHS to improving health literacy and democratizing access to health information technology. The recommendations in Health Literacy Online serve as a roadmap for achieving the Healthy People 2020 objectives to increase the proportion of quality health-related websites (Objective HC/HIT-8).

We cannot know for sure the level of health literacy of those who will visit our websites, in what context they will access them, or what device they will be using. We can, however, be ready for them. We do this by designing digital health information tools that are broadly accessible and available to all Americans because they have been designed with them in mind.

Thankfully, we have practical guidance like Health Literacy Online to help us in this mission.

Karen B. DeSalvo, MD, MPH, MSc

Acting Assistant Secretary for Health

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

About

About Health Literacy Online: 2nd Edition

Health Literacy Online is about broadening access to user-friendly

health information and services on the web. This research-based guide

discusses why and how to design health websites and other digital

health information tools for all users, including the millions of

Americans who don’t have strong reading or health literacy skills—as

well as those who don’t have a lot of time to find, process, and use

complex health information.

It’s written for anyone involved in creating online health content, from

start to finish—writers and editors, content managers, digital

strategists, user experience strategists, web designers, developers, and

others. The strategies and tips can also be applied widely across

disciplines.

Why This Guide

Many web users struggle with even the most basic tasks—for example,

using a search function, navigating from a drop-down menu, and scanning

a webpage for relevant information. This may not matter too much in the

context of an online news article or confusing eCommerce site. But the

stakes are raised considerably when a person is trying to sign up for

health insurance, learn about a new medical diagnosis, or look up how to

correctly install a child safety seat. And today, these activities are

more likely to occur online than off.

How easily users can accomplish health-related tasks online depends

largely on the quality of the websites we create. This guide represents

more than a collection of recommendations; it reflects an approach to

responsible digital design and development that:

- Prioritizes the information needs and preferences of consumers

- Involves end users as co-creators of web products

- Responds to small and large screens—and all sizes in between

- Recognizes that designing for limited-literacy users is designing

for all users

A Note on the Research

The first edition of Health Literacy Online (2010) synthesized lessons

learned from ODPHP’s original research with more than 700 web users and

the small but growing body of literature on the web experiences of users

with limited literacy skills.

In this second edition, we’ve updated the recommendations to reflect

findings from a more robust body of literature related to the cognitive

processing and online behavior of adults with limited literacy skills

(see section 1), as well as additional original ODPHP research conducted

during the past 5 years. As with the first edition, we build on the

principles of web usability described in the Research-Based Web Design

and Usability

Guidelines

developed by HHS in partnership with the General Services

Administration.

In addition, we’ve included new considerations for mobile devices. A

growing subset of Americans only access the web via a phone or mobile

device, and many of these users are likely to have limited literacy

skills. Like the rest of the recommendations in the guide, the

guidelines for mobile are based on best practices in the literature and

original testing conducted by ODPHP. Fortunately, many of the strategies

employed to improve the online experience for users with limited

literacy skills—such as putting the most important information first and

simplifying navigation—are the same best practices for mobile devices.

In section 6, we offer specific tips for involving web users with

limited literacy skills in the design and testing of health websites.

Throughout the guide, we incorporate quotes from web users with limited

literacy skills who participated in our usability studies. These quotes

speak to the valuable role web users play in writing and designing

effective websites.

Health Literacy Online: Key points

- As many as half of U.S. adults have limited literacy skills. Even

more Americans—up to 9 in 10—have limited health literacy skills.

- Literacy skills affect how people find, understand, and use

information on the web. Users may get distracted easily, give up

quickly, and struggle with dense text and complex navigation. This

is true across devices.

- The simple strategies described in this guide—like increasing font

size and using bulleted lists—can break down literacy-related

barriers and increase a user’s odds of success.

- Designing with limited-literacy users in mind results in health

websites that are easier to use for everyone.

1. What We Know About Users with Limited Literacy Skills

Introduction

There’s a growing body of literature related to the cognitive processing

and online behavior of adults with limited literacy skills. In this

section, we outline what we know about how literacy can affect a user’s

ability to read, process information on a screen of any size, and

interact with technology.

The bottom line: Literacy skills can impact virtually every aspect of

using the web.

1.1 Reading and cognitive processing challenges

Cognitively speaking, reading is a lot of work—it involves both decoding

and understanding text. First, a user has to “decode” the text by

assigning meaning to the words. Next, a user has to comprehend the text

by stringing the words together to understand what the author is trying

to communicate in a particular sentence or

paragraph.1,2,3

Users with limited literacy skills have more problems with short-term

and working memory than users with higher literacy

skills.4 They may struggle to decode challenging words

and remember their meanings.3 If a webpage has a large

amount of content, users may not be able to remember it all.

Furthermore, what they do remember may not be the most important

information.

Users with limited literacy skills often describe themselves as reading

well or very well.3,5 However, data from

eye-tracking and usability studies paint a different picture.

According to these studies, users with limited literacy skills generally

read more slowly, and reread words, sections, or elements on a website

(like buttons or menus) in order to understand them.3

And depending on the situation, limited-literacy users may:

- Skip words or sections, or start reading in the middle of a

paragraph3,7,8,9

- Try to read every word because they can’t effectively scan and draw

meaning from

content3,7,10—this is

more common when users are reading something very important and they

feel the stakes are high

These strategies used by users with limited literacy skills reinforce

the importance of creating simple content that won’t overwhelm readers

with too many words. Dense “walls of words” can trigger limited-literacy

readers to skip content altogether—or they may try to read every word on

the page while struggling to understand what they’re reading.

Additionally, online forms present a unique set of challenges for

limited-literacy users. Users need to read the instructions and the form

field labels, and then either spell the answers to questions or read and

select from multiple-choice answers.3 This is a lot to

ask from users with limited literacy skills.

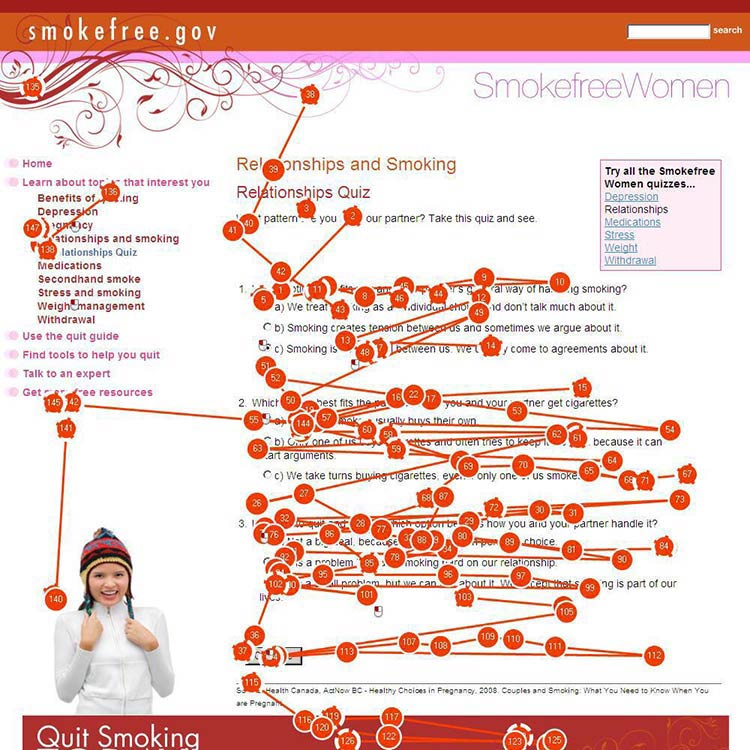

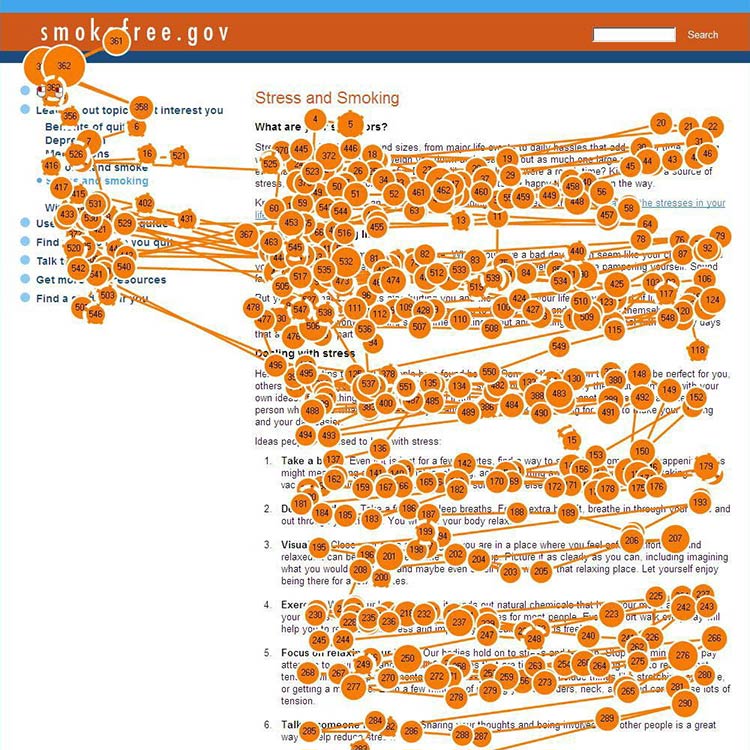

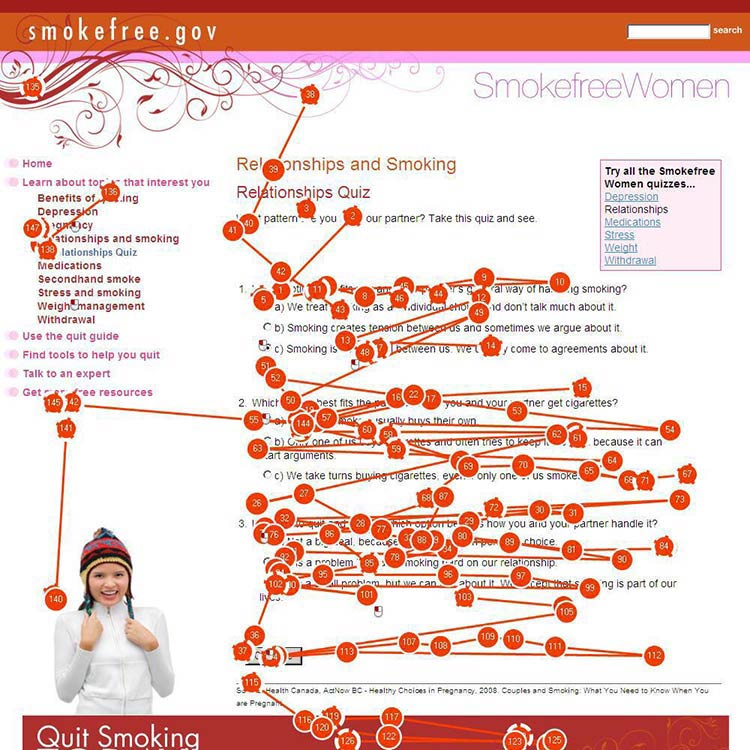

Figure 1.1

Gaze path of a reader who does not have limited literacy skills skimming a page.

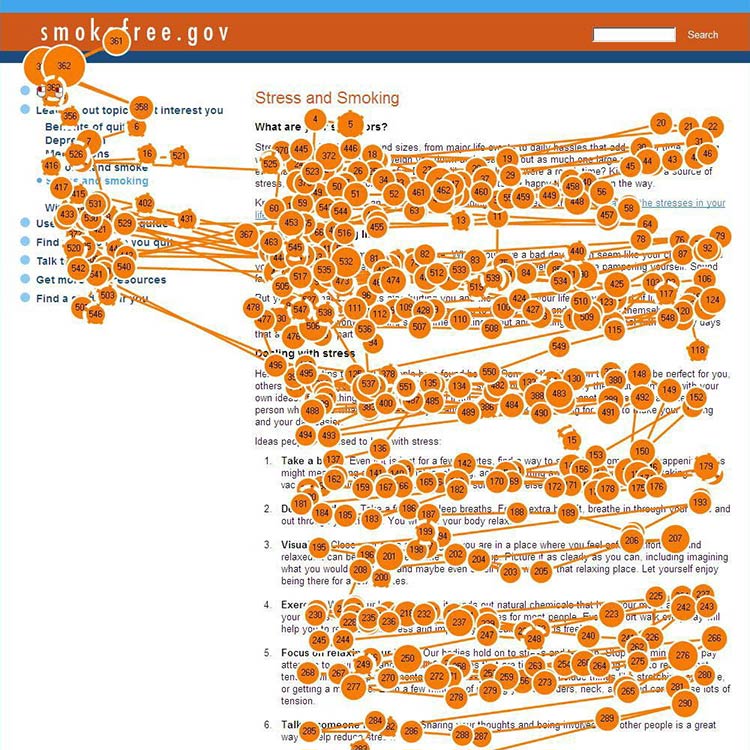

Figure 1.2

Gaze path of a user who has limited literacy skills reading (and re-reading) every word.

Figure 1.3

Gaze path of a user with limited literacy skills reading only the text that looks easy to read.

1.2 Understanding navigation

When navigating a website, users with limited literacy skills tend to:

- Get distracted by extra words and elements of a website (like links

and icons)3,11

- Navigate in a linear fashion and backtrack

frequently4,10

- Choose the first answer they find, without checking if it’s

correct—and have a hard time telling the difference between high-

and low-quality

information3,10,12

- Have trouble recovering from mistakes10

When reading, users with limited literacy skills focus on the center of

the screen. Once they shift their focus from the navigation to the

center of the screen, they’re unlikely to look back to the navigation to

solve a problem or change course if the content isn’t meeting their

needs.10,13

1.3 Using search

Using a website search function can be challenging for people with

limited literacy skills. Typing in a search term requires (somewhat)

accurate spelling—and some search engines help with spelling better than

others. Reading and comparing search results to identify the best option

is a cognitively challenging task.

As a result, compared with users with advanced literacy skills, users

with limited literacy skills:

- Spend more time on information search

tasks3,10

- Are more likely to give up if they can’t find information

quickly10

- Have a hard time thinking of search terms14

- Tend to only click 1 or 2 links in the search

result14

- Add terms to refine a search instead of changing their search

strategy15

The ways people with limited literacy skills tried to find information

differ from user to user.10

Example

In previous healthfinder.gov usability testing, the team observed 5

users while they searched for information in 5 completely different

ways. Some used the left navigation menu, while others used the homepage

buttons or the search bar.

1.4 Mobile considerations

Users with limited literacy skills are likely to access the web on

mobile devices—more than 90% own a mobile phone.16 We

also know that users with lower incomes, users with less education, and

minority users are especially likely to access the internet primarily

from their mobile phones.17

Research shows that people with limited literacy skills find it easier

to learn how to use mobile devices than desktop

computers.18

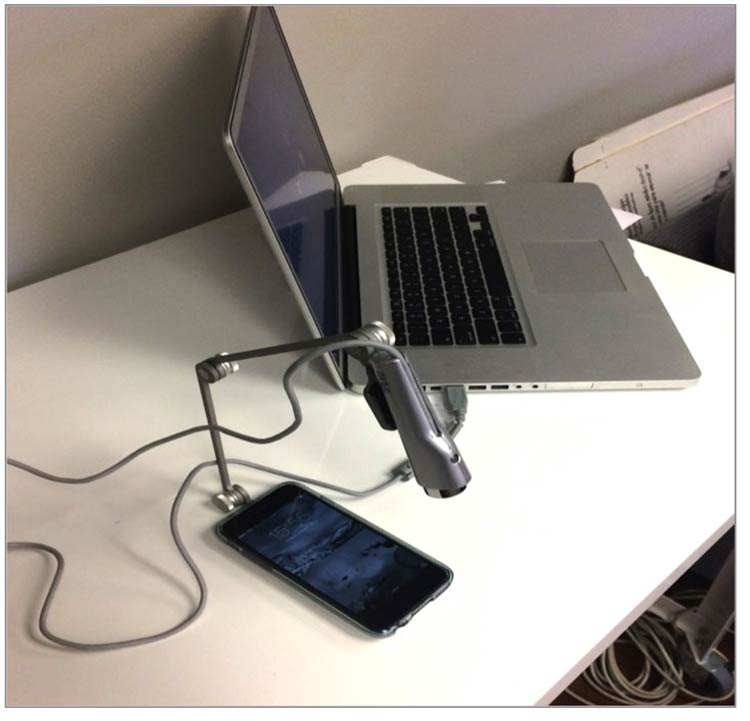

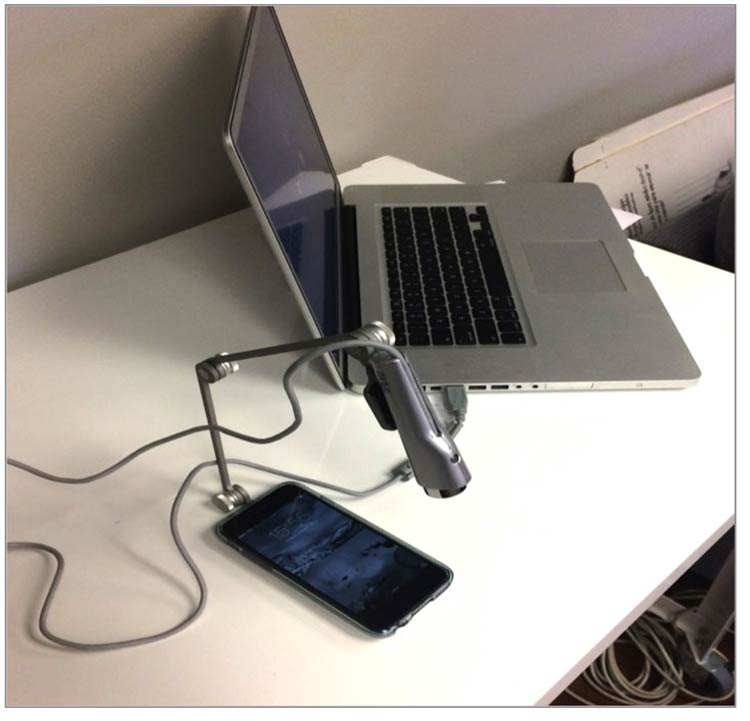

Figure 1.4

When we tested healthfinder.gov on mobile in March 2015, users navigated through health topics much more easily on their mobile devices than on a desktop computer.

Additionally, mobile screens can make reading easier for users with

reading disabilities. For this population, both speed and comprehension

may improve when reading on a mobile screen. Studies suggest this may be

because of line length—lines on mobile devices are inherently

short.19

All of the best practices set forth in this guide enhance mobile

usability. However, there are some specific considerations to take into

account when designing online health information for mobile devices.

Challenges of mobile display

Because we know that so many users with limited literacy skills are

accessing information on mobile devices, it’s very important to consider

the challenges presented by mobile display.

In spite of the fact that many users with limited literacy skills may

ultimately find mobile easier to use than desktop computers, they still

struggle with elements of navigation on mobile devices, like:

- Following hierarchical navigation

- Knowing where to look for information

- Using scroll bars within menus

- Using a single button (like the iPhone menu button) for a variety of

different purposes depending on context

- Using a small keyboard to enter text20

In general, mobile content can be twice as difficult for all users to

digest.21 Part of this is because it’s harder to

understand complicated information when you’re reading on a tiny screen,

like an iPhone.21

Additionally, mobile device users are constantly scrolling because they

can’t see all the information on the page at once. That means users are

moving around the page to refer to other parts of the content instead of

simply glancing at it as they might on a desktop screen. This can

negatively affect users’ understanding.22 The constant

need for scrolling:

- Takes more time

- Diverts users’ attention

- Introduces the problem of reorienting position on the

page22

Summary

It’s critical that we understand and anticipate the online behavior of

users with limited literacy skills—including what kind of devices

they’re using to view web content. Even users with high literacy skills

may find reading and using the web more difficult when they are sick,

stressed, or tired. Designing websites with these behaviors in mind will

make the web a better place for all of us.23

On the journey to better user experience, simplifying content is a

logical place to start.

In the next section, we cover the basics of writing actionable, engaging

plain language content for the web.

2. Write Actionable Content

Introduction

Writing for the web is different than writing for print. Most web

users—including those with limited literacy skills—are looking for

specific information or an answer to a question.24 They

typically don’t stay very long on a page. In fact, the average time

spent on a page is usually 15 seconds or

less.24,25,26

When it comes to health information, web users want to quickly and

easily do 2 things:

- Understand the health problem or behavior

- Find out how to take action—in other words, what they can do to change

their behavior or address the

problem27,28,29

Content is the most important element of your

website.24,30 No matter what the literacy

level of your audience is, always aim for health content that is:

- Brief and to the point

- Actionable and engaging

When you write actionable content, it means that you’re focusing on

health behavior: tell users what you want them to do and give them steps

to do it.

Engaging users means presenting content in a way that motivates them to

take action. Examples of engaging content include:

- Interactive tools

- Checklists

- Conversation tools

High levels of engagement with online health information can lead to

health behavior change.31

Remember, plain language alone is not enough. If you want users to

adopt healthy behaviors, you also need to write actionable health

content.

2.1 Identify user motivations and goals. Why are they here?

Motivation drives the search for health information and influences

users’ performance on a website.32,33

Understanding users’ motivations will help you write actionable,

targeted health content to meet your audience’s information needs and

expectations.

Users want the answer to a question.

Keep in mind that most web users have a specific goal in mind. Usually,

they’re trying to answer a

question.7,8, 24 Conduct

research with your users to find out what that question is—ask them what

they want to know. Then decide on the best way to give them that

information.

You can get basic information about your users online.

The best way to understand users’ motivations is to talk to them, but

you may be able to find some of the basics about an audience—like

demographic information—online. (Learn more about how to conduct

research with users with limited literacy skills in section 6.)

For example, ODPHP’s research identified several common motivations for

users who seek online health information. From this research, we know

that many users go to the web to:

- Learn about a health problem affecting them or someone they know

- Find out whether they have a health problem or reason to be concerned

- Learn how to prevent health problems32,33

Expect users’ motivations to change.

Studies have also found that what’s driving your users tends to

shift—often frequently.24 With that in mind, make sure your content meets

the different goals users may have for seeking health information.

The formula below was developed based on the motivations of users with

limited literacy skills. It’s designed to move users from “I want some

information about a topic” to “I want to do something about it.”

Follow this proven formula for presenting health promotion information:

- Describe the health behavior

- Describe the benefits of taking action

- Provide specific action steps

Quote

Quote

“Get my attention. Then get to the point.”

2.2 Put the most important information first.30

Many users with limited literacy skills read only the first few words on

a page or paragraph. If they think the content will be easy to get

through, they may keep reading. If they’re overwhelmed and think it

might be too difficult, they’ll skip to a different spot on the

page.7,27,28,34,35,36,37

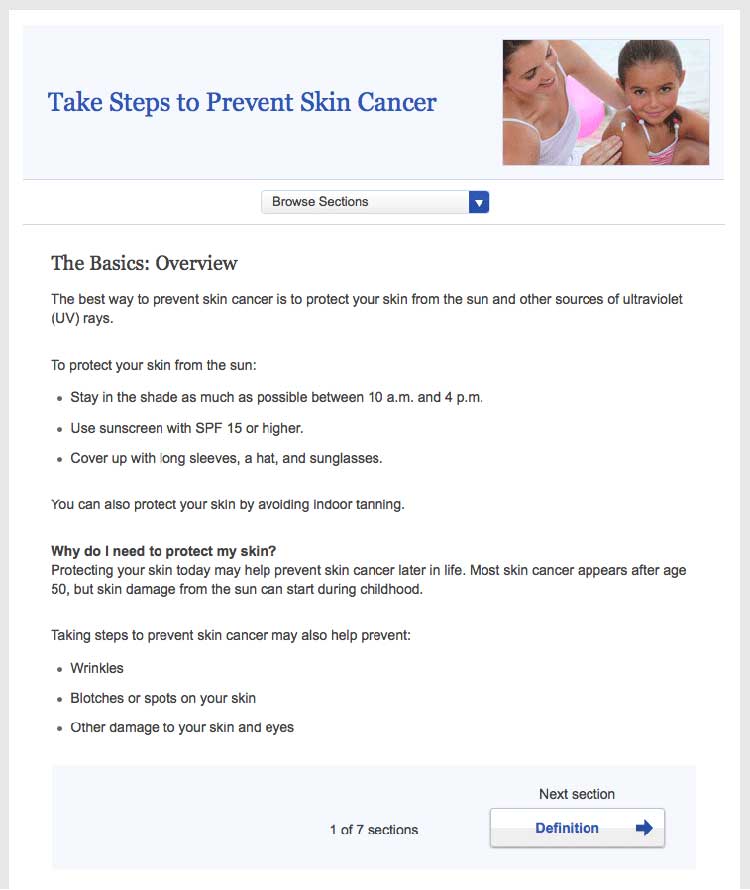

Figure 2.1

This healthfinder.gov topic puts the most important information about preventing skin cancer first. Additional information comes after the basics.

By putting the most important information first, you’re also structuring

your content for mobile users—and for busy users no matter their

literacy level or the device they’re using. Eye-tracking data shows us

that all users tend to read content at the top of a webpage and lose

interest quickly if the information doesn’t seem relevant to them.25

2.3 Describe the health behavior—just the basics.

Start by introducing the behavioral objective. Users want actionable and

specific behavioral

guidance.28,38,39,40 In

other words, tell users both what to do and how to do it. Focus on

behavior rather than background information and statistics. Remember,

it’s important not to overwhelm your users.

Think “need to know” vs. “nice to know.”

Health information doesn’t need to be comprehensive. Instead, usability

research has shown that many users prefer to learn “just the basics”

about a health topic.30 What do your users need to know to take

action? Keep your information direct and to the point. People who are

motivated to find more information will dig further.26

Quote

Quote

“Just tell me what I need to know.”

Example

- Before:

- Blood pressure is the force of blood against the walls of

your arteries. Blood pressure should be checked often.

- After:

- Check your blood pressure every 2 years, especially if you

are age 40 or older.

Figure 2.2

The first sentence on this page from healthfinder.gov

includes the behavioral recommendation (regular screenings for people

ages 50 to 75).

Quote

Quote

“I like this website because it gives you the

information you want right away. It gives you the basics, not too much

to read.”

2.4 Stay positive. Include the benefits of taking action.

Users overwhelmingly prefer a positive tone, so make your case without

being too negative. During card-sorting exercises, users prioritized

information on motivators and overcoming barriers to behavior change —

not information about the risks and barriers

themselves.8,27,29,39,41,42,43,44

Give users motivation to make a change.

Users want to know what they can gain from changing their behavior.

Example

Physical activity can improve your heart health—not to mention help you

feel better in your daily life!

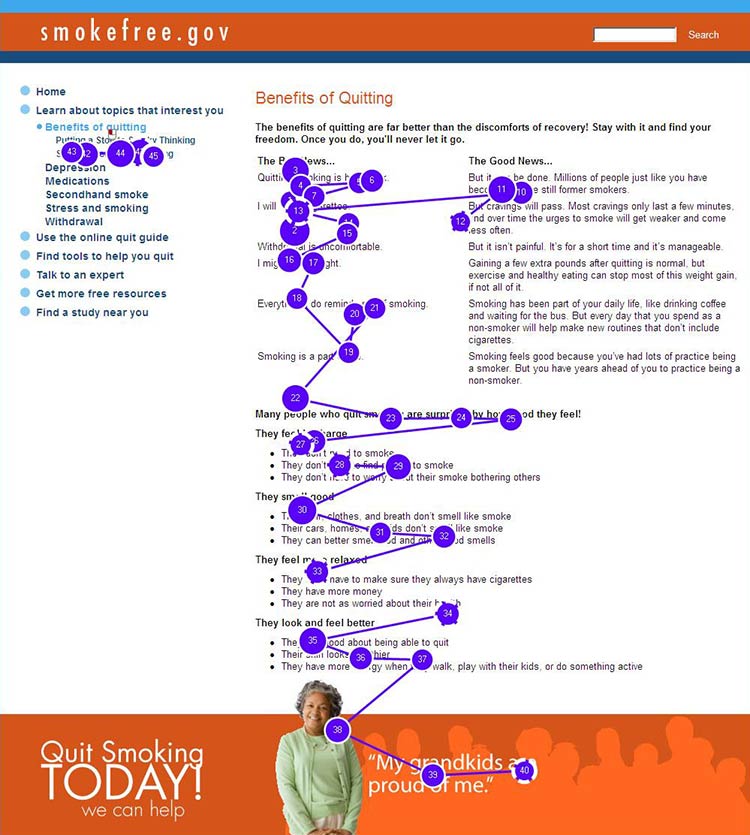

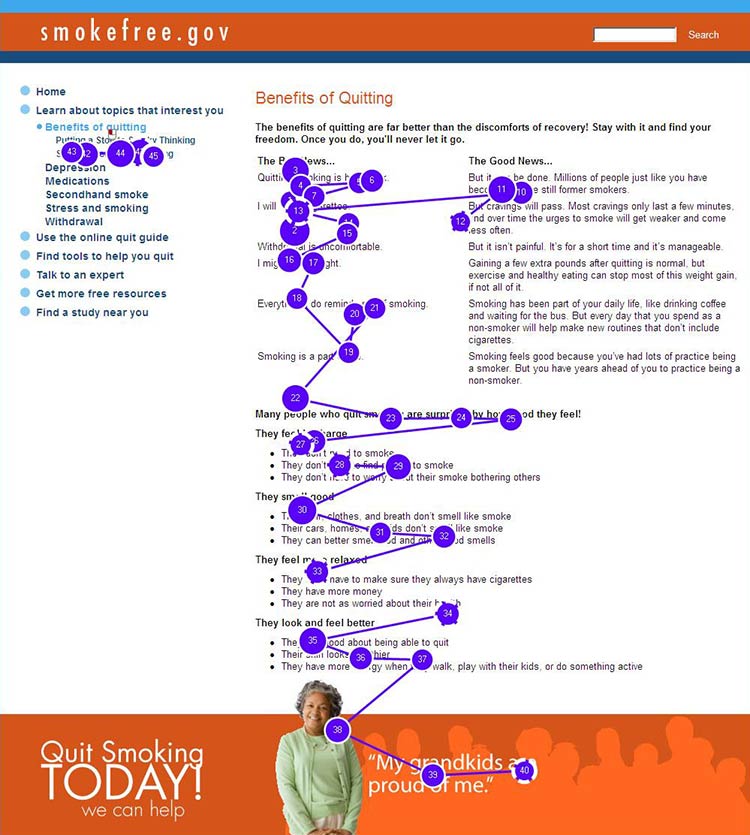

Figure 2.3

This healthfinder.gov page clearly lists the benefits of

quitting smoking instead of focusing on the risks of continuing to

smoke.

Be positive.

Instead of telling people what not to do, give users positive reasons

to change their behavior.

Example

- Before:

- Never ride a bike without a helmet.

- After:

- Wear a helmet every time you ride a bike.

Try this

When choosing language, limit the use of “don’t.” This

automatically sets up negative framing. Additionally, try not to use

“should”—it can sound “preachy” or condescending.

Focus on tips and tools for overcoming barriers—not on the barriers

themselves.

Users need to overcome many perceived and actual barriers on the road to

health behavior change. Be realistic—it’s important to acknowledge these

barriers and continue to offer encouragement and

motivation.45

Example

Quitting smoking is hard, but millions of people have done it

successfully. In fact, more than half of Americans who have ever smoked

have quit. You could be one of them!

2.5 Provide specific action steps.

Give users the tools they need to get started. Users are looking for

action steps, especially things they can do immediately.28,38,39,40,41

It’s not enough to tell users what to do. You also need to tell them

how to do it.

Break behavior into small steps.

Breaking behaviors into small, manageable steps gives users choices

about which steps feel realistic and doable. When possible, lead with

steps users can take right away.

Figure 2.4

This healthfinder.gov page has specific action steps—they’re

concrete and manageable.

Breaking behaviors into small steps improves users’

self-efficacy.28,38,39,40,41

Try this

Next time you’re creating messages, incorporate personal

stories of people who have made a healthy behavior change to strengthen

your messaging. Storytelling can go a lot further than statistics when

it comes to improving your reader’s self-efficacy. Even adding a single

quotation from someone your reader can relate to can make a big

difference.

Create interactive content.

As part of your action steps, engage users with interactive content like

menu planners, printable checklists, and questions to ask a doctor

(learn more in section 5).

Quote

Quote

“This is good information because a lot of

times, I take information to the doctor and ask questions about diet

issues, what to avoid, and medications.”

Explain the “why” of the action step.

Tell users the reason behind what you’re asking them to do. This will

help them understand why it’s important that they take the step.

Example

Keep a food diary. Knowing what you eat now will help you figure out

what you want to change.

2.6 Write in plain language.

Developing website content in plain language means that your users will

be able to understand what you’re trying to say the first time they read

it.47

Keep paragraphs and sentences short and simple.47

Try to keep sentences to 20 words and under.30 Try to keep paragraphs

to 3 lines or less.7,24,48

Always use language that is familiar to your

users.7,8,24,27,30,35,49

Avoid jargon terms when you can. Choose language that your users can

relate to.

Use the active voice.

Write in the active voice.47 Writing in the active voice means that

the subject of your sentence performs the action. Active sentences:

- Are more actionable and direct

- Are easier to understand

- Generally require fewer words24,30,37,50

Example

- Passive:

- Tests may be needed to find out what’s wrong.

- Active:

- You may need a test to find out what’s wrong.

Define complex terms.

When introducing a medical term, clearly define the term the first time

you use it. Define the word in context rather than using a glossary or

scroll-over definition.

Example

Your primary doctor may refer you to a neurologist. A neurologist is a

doctor who treats problems related to the brain and nervous system.

Think about whether it benefits the user to learn a jargon term—or if it

makes sense to work around it. For example, a person with epilepsy needs

to know the term “neurologist,” while in a different context it may be

enough to say “specialist.”

If the most accurate word is an unfamiliar medical term, incorporate a

plain language definition into the text the first time you use

it.51 Consider making the definition part of the

sentence or placing it between em dashes.8

Example

The medicine can cause vomiting—throwing up—if you take it on an empty

stomach.

Use everyday examples to explain medical or technical concepts.47

Always choose words and images that your users can relate to.

Example

When you get a mammogram, the nurse will place your breasts between 2

plastic plates and take a picture of each breast.

Write in a friendly, conversational tone.

Formal language can make health content feel less accessible to your

user,37 so write how you speak. Use contractions.52

Use second-person pronouns when you can to speak directly to your

reader.47

Quote

Quote

“I like [this website] because it’s easy for

everyday people like me to read. No big words or medical terms.”

2.7 Check content for accuracy.

Have a subject matter expert or panel periodically review your health

content for accuracy. Post the date the content was last reviewed and

the reviewer’s name and contact information. This gives your content

more credibility with users.

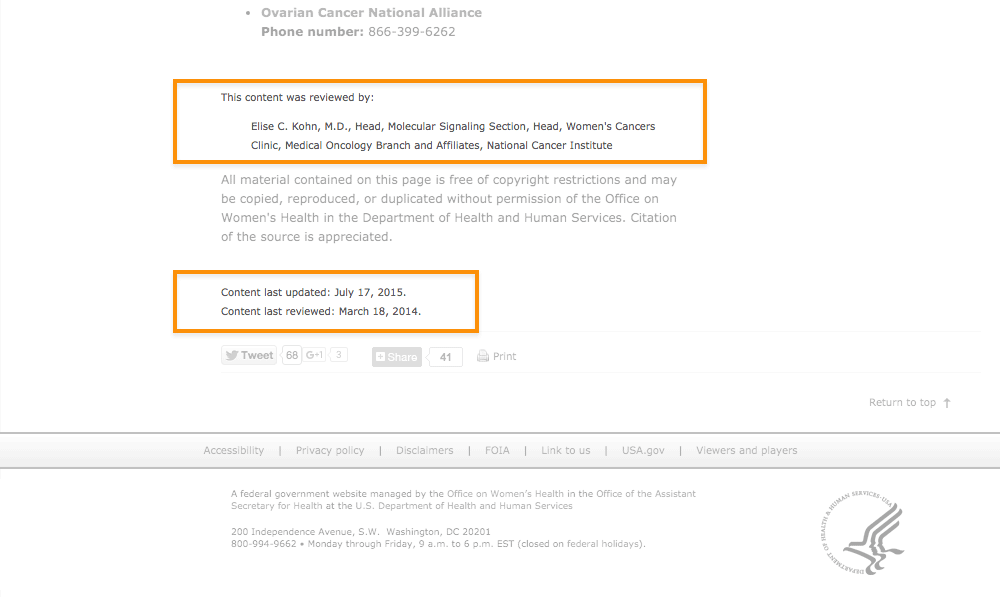

Figure 2.5

The date the content was last reviewed and the name and contact

information of the reviewer are both clearly displayed at the bottom of

this page from the Office on Women’s Health.

Develop a style guide.

Use a style guide to keep your content consistent. Style guides are

especially helpful when writing about something like health—a subject

that includes many topic-specific words and phrases. A content style

guide will help you establish a streamlined set of health-related terms

that users will come to recognize in your content.

A style guide also lays out the rules for writing content for a specific

website. A style guide can help you keep track of grammar, spelling, and

writing preferences. (For example, is it “website” or “Web site”?) You

also can use a style guide to keep track of heading and font size.

A style guide is an evolving document. Writers and editors will likely

add to it over time. Be sure to keep it easily accessible.24 Many

organizations use a wiki for their online style guide because it’s easy

to update and share. (A wiki is a website that allows for the easy

creation and editing of web documents.)

For tips on creating a content style guide, check out this resource

from

digitalgov.gov.

Summary

On the web, and especially on mobile devices, users want to find the

information they need as quickly as possible. Regardless of your

audience’s literacy level, keep your content short and to the point, and

write in plain language.

But plain language isn’t enough—if you want your users to change their

behavior, write health content that’s actionable and engaging. When you

give your users clear action steps—and motivate them with engaging

content like interactive tools and checklists—they’re more likely to

follow through.

In the next section, we discuss best practices for design and layout to

make your content easier to read and give it an approachable, inviting

look.

3. Display Content Clearly on the Page

Introduction

Writing easy-to-read web content is only the first step. If you want

people to understand the content, it needs to look easy to read—both

on desktop and on mobile.

Even health content written in plain language can look overwhelming if

there’s too much text in a paragraph or not enough space on the

page.7,24,35,49

And if your site doesn’t display or function well on mobile, users on

mobile devices may give up before they even get to your content.

Web design and content go hand in hand. Use white space, layout, font,

and color to help users understand the content on your website.

Try this

When developing your health content, imagine you’re

writing for a mobile screen. This will naturally force you to take into

account many of the best practices outlined in this section. By writing

for a mobile display, your content will be simpler and easier to

understand across all screen sizes.

3.1 Limit paragraph size. Use bullets and short lists.

It’s very important not to overwhelm your users with content regardless

of screen size. These principles apply not only to mobile devices, but

to desktops and laptops as well. All of the following can trigger web

users with limited literacy skills to skip over content:

- Dense “walls” of text

- Long sentences

- Paragraphs with multiple numbers in the text

- Long words

- Paragraphs with more than 3 lines7,24,28

The takeaway here is that users will skip information that looks

difficult to read regardless of how simply it’s written or how important

it is.

Additionally, write for users’ limited working memory. Breaking up

content into manageable “chunks” or bulleted or numbered lists can help.

For example:

- Use clear, stand-alone sections or “chunks” of text with

headings.24,30,53

- Make sure each chunk of text has only 1 theme or

idea.54

- Turn sentences into lists when possible.24,30

- If your list has more than 7 items, break it up into several

sub-lists.54

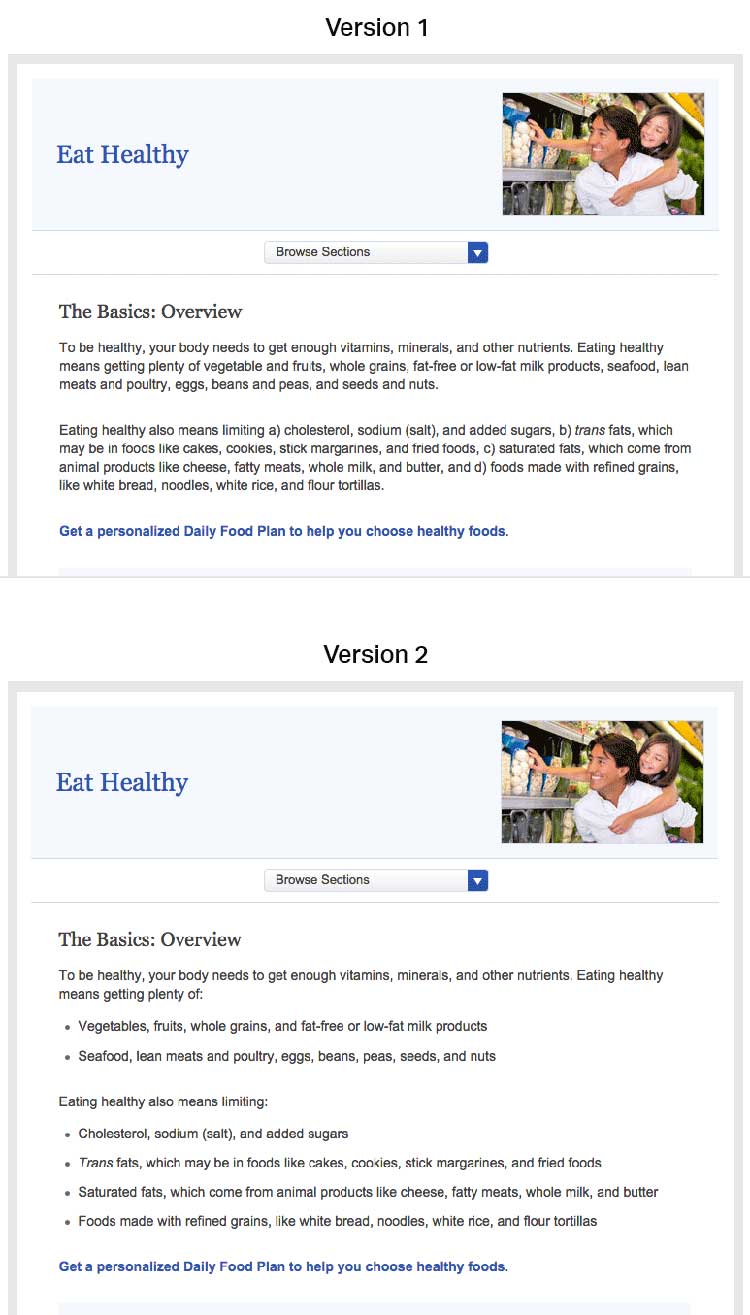

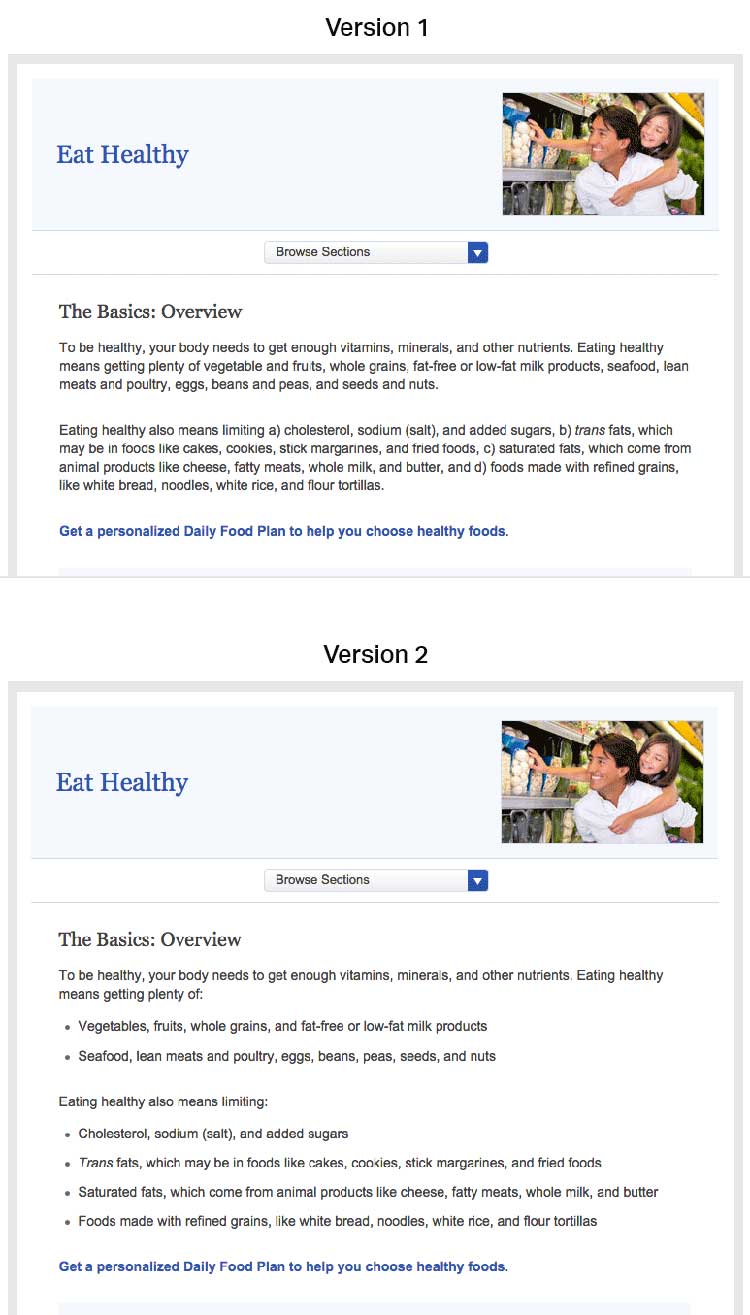

Figure 3.1

Compare these webpages from healthfinder.gov. Users are less

likely to read content presented in long paragraphs of text, as in

version 1. Version 2 is easier to read because it uses bulleted lists

and smaller “chunks” of text.

3.2 Use meaningful headings.

When users scan webpages, they often only read the headings to figure

out if the content is relevant to them. It’s important to make your

headings as specific as possible24,30—try to include keywords to help

users find the information they need.

Including keywords in headings also makes it more likely that search

engines will show your content in search results. Search engines show

sites where keywords appear in the web address, title, page headings,

and links before they show websites with keywords that only appear in

content.

Try this

Start headings with verbs when you can. This helps set you

up to write actionable content.

Use subheadings.

Adding a subheading, or “teaser” text, underneath each heading can give

the user additional clues about what to expect from your content.

Suggestion

Main heading: Get Active

Subheading: Aim for 2 hours and 30 minutes of activity a week.

Consider question headings.

When appropriate, try using questions as headings.24 Use “I” and “me”

to reflect the voice of the user.

For example, when discussing mammograms, common questions include:

- How will this benefit me?

- How much does it cost?

- What happens if the doctor finds something wrong?

- How often do I need to get tested?

- Does it hurt?

- Are there any risks associated with the test?

- What if I don’t have time?

Place headings properly.

Make sure your headings don’t “float” on the page (floating happens when

there’s too much white space above and below the heading). Make it clear

which chunk of text the heading corresponds to—leave more space above a

heading than between the heading and the text that comes after it.24

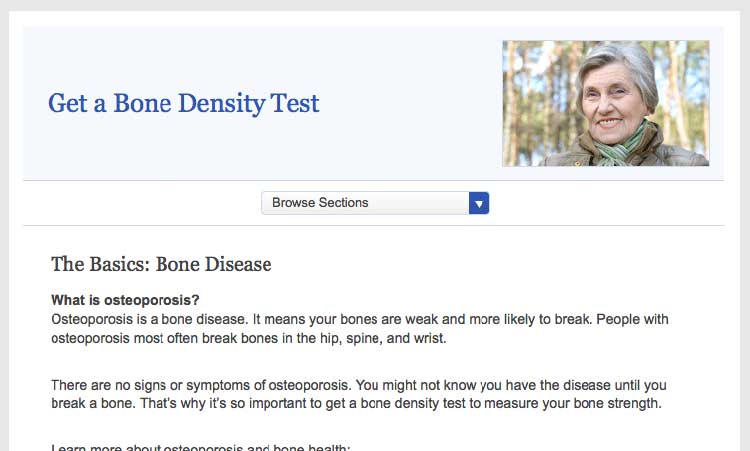

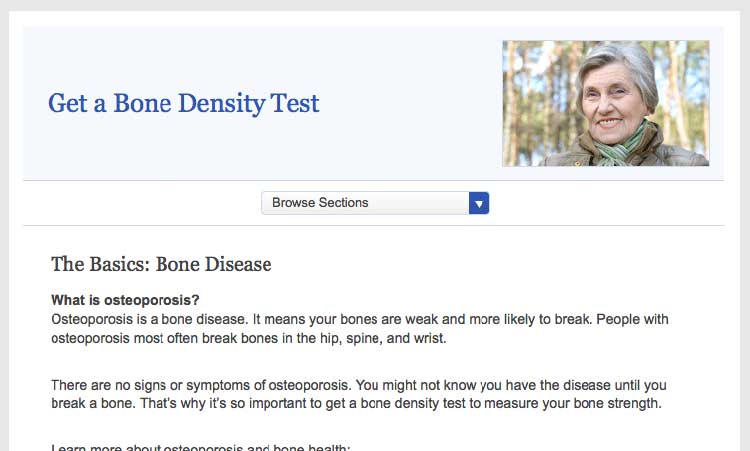

Figure 3.2

On this healthfinder.gov webpage, information about

osteoporosis is organized using questions as headings. There’s more

space before the heading than after, creating clear “chunks” of text.

3.3 Use a readable font that’s at least 16 pixels.

The font you choose is important because it affects your site’s

readability. Below, we list the most important elements that contribute

to making a font readable.

Size

Choose a font that’s at least 16 pixels, or 12 points. If many of your

users are older adults, consider using an even larger font size—19

pixels or 14 points.6,24 A small font size is more

difficult to read, especially for users with limited literacy skills and

older adults.

Quote

Quote

“I like when I can read the words without my

reading glasses.”

Set up your site so that users can adjust the size of the text on the

page.24 Web designers can make this possible by using what’s called

relative type size. However, it’s still important to test out your

website with different font sizes to make sure it’s still easy to read

and navigate. Always check how your content looks on a mobile device, as

well—newer, high-resolution screens that render more pixels per inch can

make text look smaller.

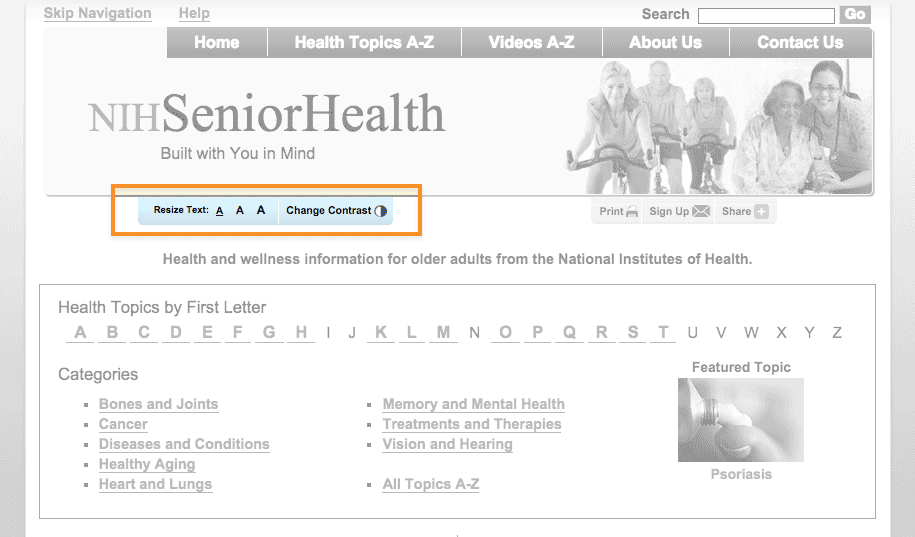

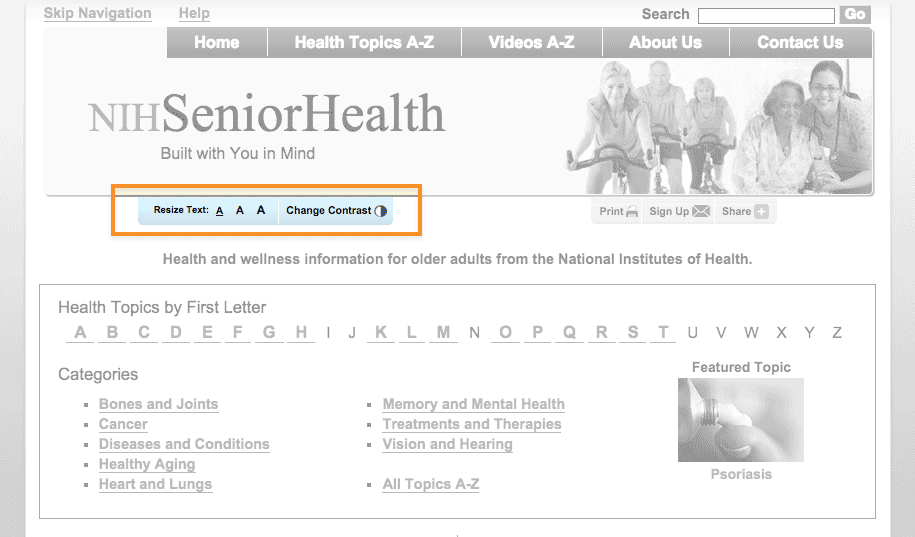

Figure 3.3

NIH SeniorHealth includes a toolbar on every page that allows

users to change text size and adjust color contrast (colored text on a

black background).

Simplicity

Unusual fonts with unnecessary flourishes can be hard to read. Choose a

mainstream font that will feel familiar to your users.30

It’s easier to read text printed in simple, familiar fonts like

Verdana.

Example

Lucida Handwriting

“Regular physical activity is good for your health. Get tips to help you

get more active.”

Verdana

“Regular physical activity is good for your health. Get tips to help you

get more active.”

Also, while you can use a different font for headings and body content, don’t use more than 3 fonts on a page. Use fewer, simpler fonts to make your page look more cohesive.55

Serif or sans serif?

There’s been a lot of debate about which type of font is easier to read

online—and overall, the research is inconclusive.30,56

However, some evidence suggests that serif fonts may make reading on the

web more difficult for users with reading

disorders.56,57

The bottom line: Choosing sans serif fonts is best practice when writing

for the web.24,57,58 Use a familiar sans serif font like

Verdana, Lato, Open Sans, Proxima Nova, or Source Sans.

Line height

Line height (also called leading) is the vertical distance between lines

of text. Common line heights in word processing include:

- “Single spaced” (line height of 100%, equal to the font size)

- 1.5 lines (line height of 150%, equal to 1.5 times the font size)

- “Double spaced” (line height of 200%, twice the font size)

Some word processors—and many web design programs—will give you even

more options.

To maximize readability, use a line height that is 130% to 150% larger

than the font size.56 This helps keep users with limited literacy

skills from losing their place in the text as they start reading a new

line—and makes it easier for them to use their fingers to help keep

their place.

Example

It’s best to specify leading of about 140% (the middle option

below).59

100% Leading

“Making small changes to your eating habits can make a big difference

for your health. Here are some tips and tools you can use to get

started.”

140% Leading

“Making small changes to your eating habits can make a big difference

for your health. Here are some tips and tools you can use to get

started.”

200% Leading

“Making small changes to your eating habits can make a big difference

for your health. Here are some tips and tools you can use to get

started.”

Line height is also an important consideration for mobile users. When

paragraphs or bulleted lists include multiple links, extra height

between lines helps ensure that users have enough room to tap the item

they want.60

3.4 Use white space and avoid clutter.

Clean, uncluttered webpages are easier to read24,30—they’re less

distracting and less overwhelming for everyone, especially people with

limited literacy skills and very busy users.

Use white space in your content to break information into chunks. Leave

space between sections of text and around images and buttons.

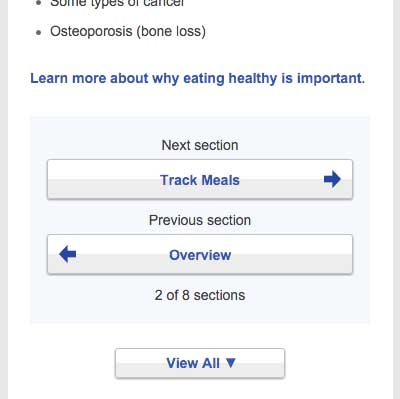

Figure 3.4

The CDC.gov homepage includes space around the logo and search

box, and under the banner image, which helps the site look clean and

uncluttered.

Figure 3.5

The health.gov homepage also has a very clean look with lots of

white space.

White space around site features also helps mobile users interact with

buttons and links without accidentally tapping the wrong place.

3.5 Keep the most important content above the fold—even on mobile.24,30,61

Users spend the most time looking at content they see

first,62 so make sure the most important and compelling

content appears above the fold. Users also judge the content they can

see to decide whether it’s worth scrolling down to see more.62

Figure 3.6

The most important content in this topic about getting tested

for HIV is visible above the fold.

Keep in mind that low literacy readers may have trouble with

scrolling—eye-tracking data shows that the need to scroll makes it more

likely that they’ll skip content as they try to find their place again

to continue reading. That’s why it’s important to minimize scrolling

when you can.63

If your content continues below the fold, the best cue to let users know

they need to scroll down is a paragraph of text that crosses the scroll

line.64 However, it’s very challenging to ensure that

this will display consistently on different screen sizes—so you may want

to consider using a scroll arrow or scroll bar

instead.65

Try this

View your website using different monitors, browsers, and

devices to see how your content displays on the screen.

Finally, be aware that users may mistake horizontal lines or large

sections of white space at the bottom of their screen for the end of a

webpage. That’s a good reason to look at your site on many devices and

screen sizes. If you find either of these at the bottom of a page,

consider making some changes—“false bottoms” might stop people from

seeing all of your content.24

3.6 Use links effectively.

The ability to link to related content is a major benefit of writing for the web. Below, we list some strategies for using links effectively in your online health content.

Limit the number of links on a page.

Users with limited literacy skills sometimes click on links instead of reading content on a page.7 Limiting how many links you have on a page can help prevent too much “link hopping”.

Think about links as exit points—include them only in places where you really want your users to exit.

Link directly to tools and resources that support your

content.28,40

Include links that allow

users to “drill down” for more detailed

information8,28,40—avoid linking to pages with

redundant content.

Here are 3 rules to follow when writing links on a webpage:30

1. Make links long enough to “grab” easily.24,50 If

your link is too short, it may be hard for users to tap or click on the

right part of the screen to select the link.

2. Use descriptive link labels so there are no surprises.24,30

Descriptive link labels tell your user what to expect from a link. Users

should never be surprised by what they find when they click on your

link. They can also help users find the right content—and improve search

engine rankings.

3. Use action verbs in link labels.8,24 Choose actionable link

labels, like “Check out these tips for getting active,” “Find out how to

eat healthy during pregnancy,” or “Read more about diabetes.” Action

verbs help users engage with your content.

Suggestion

- Before:

- Insurance Plan Locator

- After:

- Find the right insurance plan for you

Figure 3.7

Links on this healthfinder.gov webpage follow all 3 rules for

link labeling. Readers know what to expect when they click on each link.

Never use general link labels—they don’t help people know what to

expect. For example, avoid the following link labels:

- Click here

- Print

- Learn more

3.7 Use color or underline to identify links.

Display links so users will easily recognize them as clickable—and stay

consistent with presentation throughout your site.66

To follow established guidelines for displaying links:

- Use blue for unvisited links and purple for visited links unless you

have a reason to choose different colors.

- Test your color choice to make sure it stands out from the body text—and

that it’s visible to people who are color blind.50

- Underline links in main content areas—users still recognize underlined

content as a hyperlink indicator (especially users with low vision or

other accessibility issues).67

- Don’t underline items like navigation menus if their location makes it

clear that they’re links.50

Figure 3.8

NIH Senior Health uses standard link guidelines—blue and

underlined for unvisited links, and purple for visited links.

3.8 Use images that help people learn.

Including simple visuals to support written text can help users with

limited literacy skills find, understand, communicate, and use health

information.30,38,65,68,69

Choose images that support your text.

Think of graphics as a way to enhance and explain your content, not as

decorations. Also look out for visuals that might actually diminish your

content—busy, bright, or animated graphics are distracting and often

mistaken for advertisements.41

Choose realistic images.

Use realistic pictures to illustrate health behaviors and clarify

medical concepts. Users prefer photographs of “real” people rather than

illustrations or people who look like models.49 It’s also important to

show people of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. That way, more

people will be able to find “themselves” on your site—and more easily

relate to your content.

Keep in mind that people react strongly to images, so be sure to test

your site with images included. Pay attention to users’ reactions to the

images—they may surprise you.

Try this

When illustrating an anatomical or medical concept,

consider a simple line drawing—they’re often most effective.67

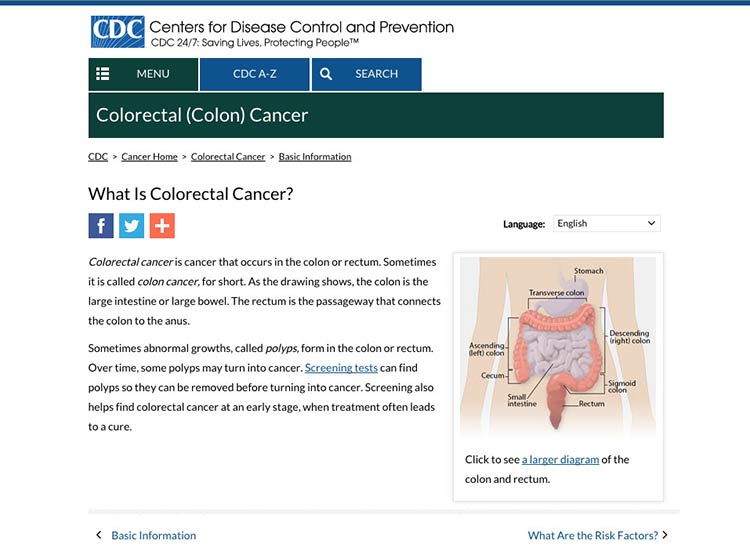

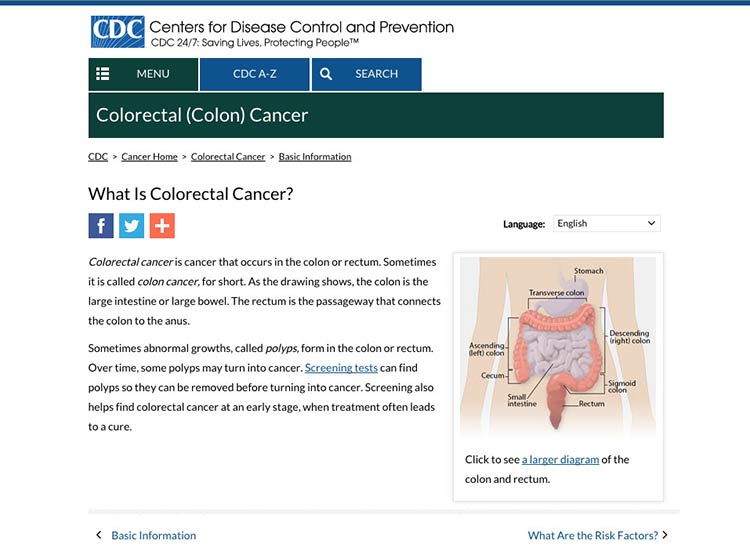

Figure 3.9

This simple line drawing and labels from CDC.gov explain the

location of the colon and rectum.

Make sure the meaning of your image is clear to all users.

Always include a descriptive caption that explains the picture.67 Use

alternative text (called an “alt tag” or “alt text”) to describe

graphics for people using screen readers.

3.9 Use appropriate contrast.

Dark text on a white or very light background is the easiest to

read.24,30 Use reversed-out text (dark backgrounds with light text)

sparingly. It’s also important to keep the background clear, so avoid

patterns and images.

Example

- Good contrast:

- Arteries are the tubes that carry blood away from your heart. Every time your heart beats, it pumps blood through your arteries to the rest of your body.

- Bad contrast:

- Arteries are the tubes that carry blood away from your heart. Every time your heart beats, it pumps blood through your arteries to the rest of your body.

3.10 Make web content printer friendly.

Many web users with limited literacy skills prefer to print pages from a

website rather than read text on a computer screen.28,30,60,65 They may

also want to share health information with family members or friends who

don’t have access to a computer or post it on their refrigerator. That’s

why it’s important to make sure your content is ready to print.

Figure 3.10

When a user clicks the “Print” button, a printer-friendly page appears. The printer-friendly version has clear headings and doesn’t include page numbers.

Quote

Quote

“I would like to print this page and show it to

family members who need this information.”

Use print links for pages designed specifically for printing.

For pages meant to be printed (like a list of questions to bring to the

doctor’s office), prompt users with a print link. Make the print link or

icon clearly visible on each page. If possible, give users the option to

print a single page, a complete section, or just a portion of the text.

Make printed content user-friendly.

Follow these design guidelines:

- Use a lot of white space, good color contrast, and clear headings on

each page.

- Specify a print style sheet that will only be used when the user

clicks to print the page.

- Design your site with fluid, percentage-based widths that allow for

printing from a range of devices.

- If your site has page numbers, make sure that printing will override

them—or give users a “view all pages”

option.71,72

3.11 Make your site accessible to people with disabilities.

All Federal Government websites must be accessible to people with

disabilities. This is often called Section 508 compliance (referring to

Section 508 of the Rehabilitation

Act).73

The guidance in Section 508 helps us design websites that work for

everyone.

Here are a few of the important considerations addressed under Section

508:

- Make sure screen readers and other assistive technologies can read

your site. That way, users with physical impairments will still be

able to access your content. Usually, this involves confirming a

logical reading order of your page, making sure important content is

near the top of what the screen reader will “see” first, and making

sure that images have appropriate alt text. You can find other

criteria in the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)

2.0.

- Mark up page titles and section headings consistently. This will

ensure that users with and without a screen reader can easily

identify the major content sections on the page.

- Check that users can navigate your site using only a keyboard.

That way, your site will still be accessible for users who have

mobility or vision impairments and aren’t comfortable using a mouse

or touch screen.

- Choose strong color contrast, especially for buttons. Many users

with vision impairments are not actually blind, but rather have low

vision or color blindness. For these users, it’s very difficult to

tell the difference between similar colors—low-contrast text

may disappear.

- Test content that requires the use of plug-ins or dedicated

software for accessibility.30 There are additional accessibility

requirements for other plug-ins that take a user out of a

web browser. It’s important to test non-HTML elements in their

application to make sure they are still accessible to all users.

Get more information about web accessibility

from the Web Accessibility Initiative.

3.12 Make websites responsive.

Today’s users expect websites to work well on every screen they

touch—whether it’s a phone, a tablet, a desktop computer, or whatever

else we haven’t thought of yet. More and more, users are accessing the

web from mobile devices. And for some—especially low-literacy

users—mobile devices may be their only means of web

access.17

With this shift in how we’re accessing web content, web designers have a

variety of options for serving content to mobile users, including native

mobile apps, web apps, and mobile

websites.74,75

For most health websites, responsive design is the best choice.

Responsive design websites show users content in a format that’s

tailored to the screen size, platform, and orientation of the user’s

device.72,73

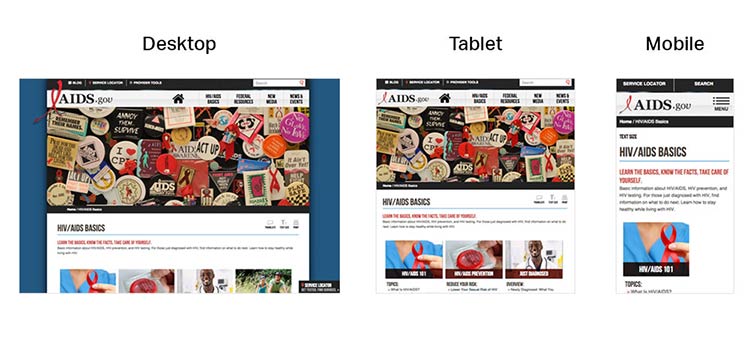

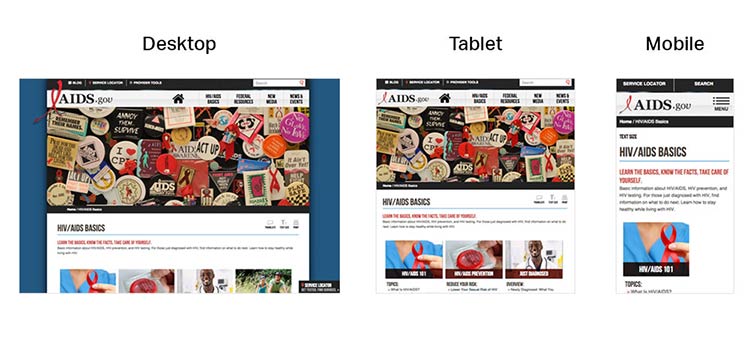

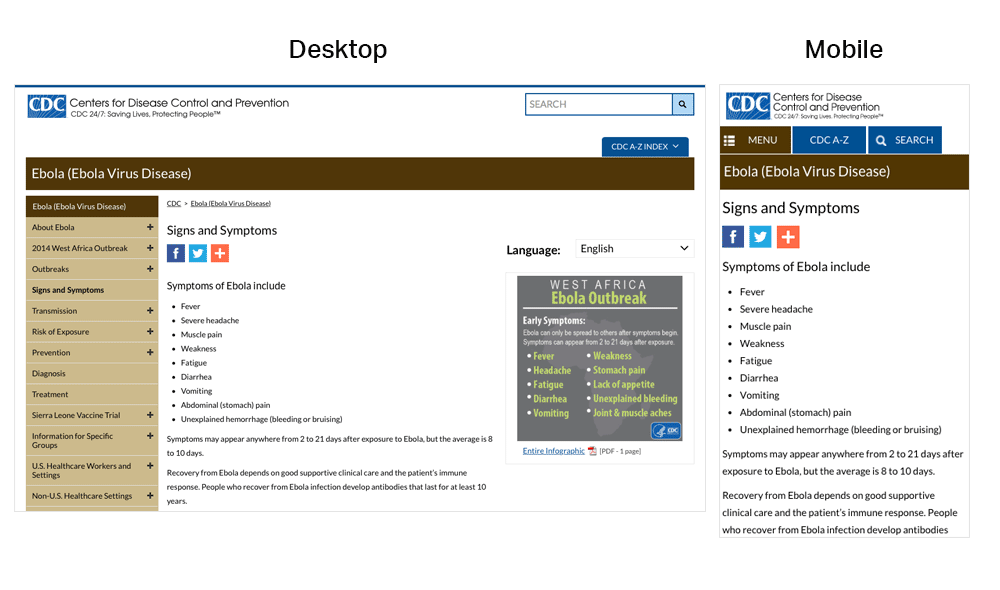

Figure 3.11

AIDS.gov’s responsive design delivers content in different

formats based on the user’s screen width.

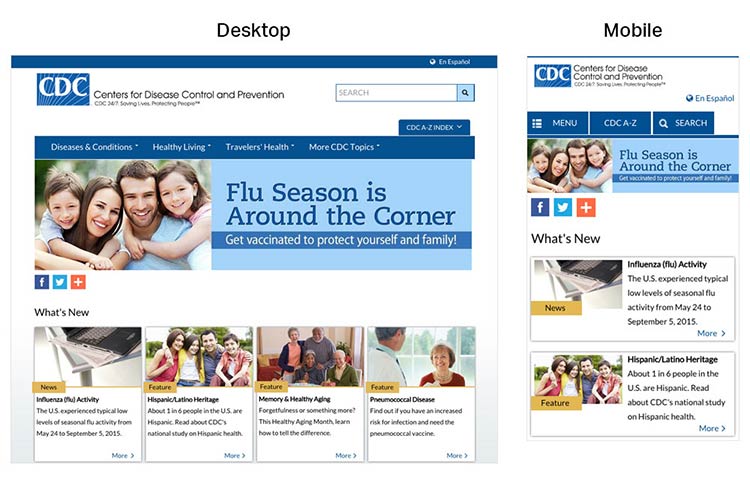

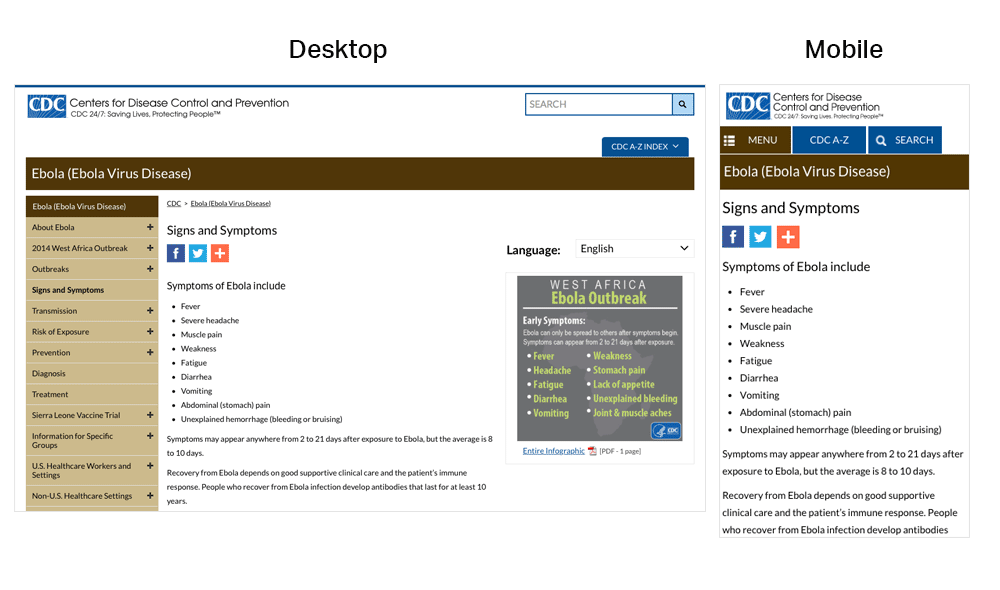

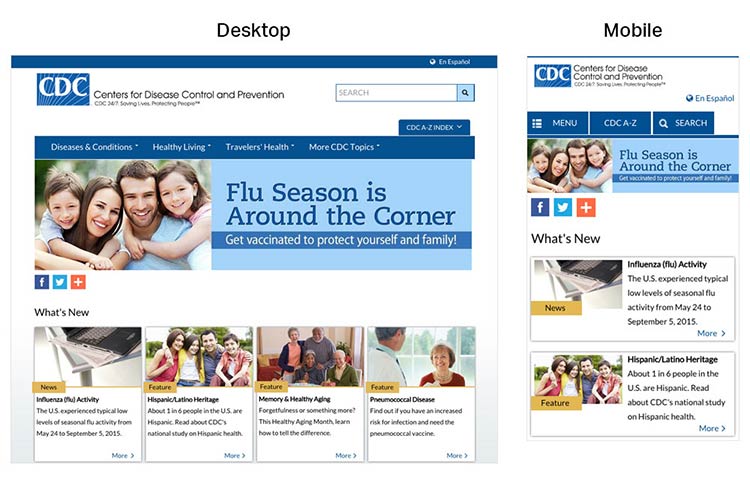

Figure 3.12

CDC’s responsive design template offers a good experience for

users on mobile. The site is reprioritized so that users don’t need to

“pinch” or zoom into content when they land on the page.

A main advantage of responsive design is that a single website can

deliver content optimized to appear on a wide variety of devices and

screen sizes. But keep in mind that responsive design is limited in that

only format—not content—can be tailored based on a user’s device. That’s

why it’s so important to develop content for the smallest screen size.

By doing so, content developers must make tough choices and create a

thoughtful, logical content hierarchy and cut (or link to) superfluous

information.

Most of the time, users won’t think about how your site was built—they

just want a seamless experience across devices.72

3.13 Design mobile content to meet mobile users’ needs.

Many of the core design principles in this guide apply to mobile design

as well as desktop, but there are some additional things to consider

when designing on mobile.

Limit the number of elements on each screen.76

Keeping your design uncluttered is especially important for mobile users

who are viewing content on a small screen. Simple screens enable users

to find what they’re looking for more efficiently.

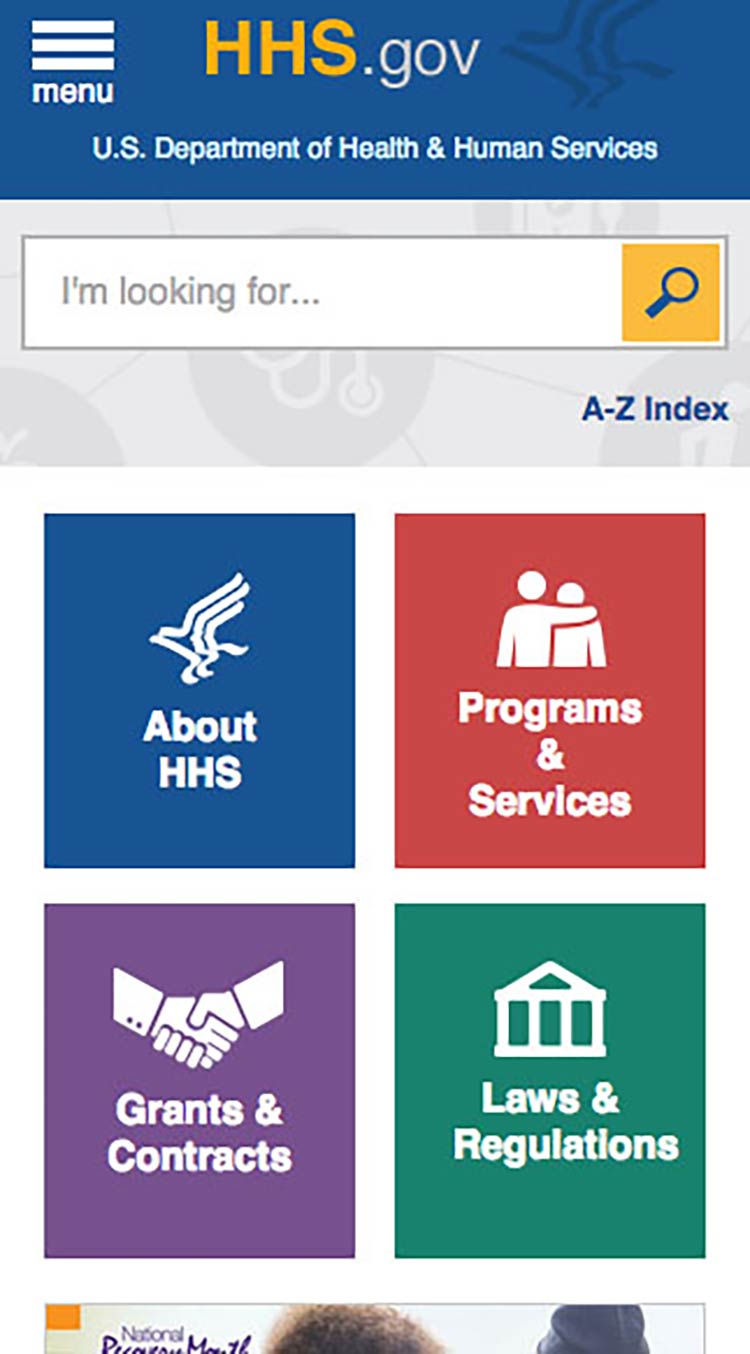

Figure 3.13

On mobile devices, the HHS.gov homepage features a simple

search bar and 4 buttons, each linked to a secondary page.

Prioritize content and features at the top of the page.

Users spend the most time looking at content near the top of the

page.77 Give limited space to elements users interact

with at the top of the page—like buttons, menus, and links—so there’s

room for content.78

Figure 3.14

On mobile devices, the CDC website prioritizes important

content at the top of the page—images and additional settings (like

language preference) are at the bottom of the page.

Make interaction easy.

Mobile devices have smaller screens, so selecting a button or typing may

be more challenging than on a desktop computer. Additionally, mobile

interfaces can be challenging for users with physical conditions that

affect their fine motor control (how precisely they can click or touch

things).

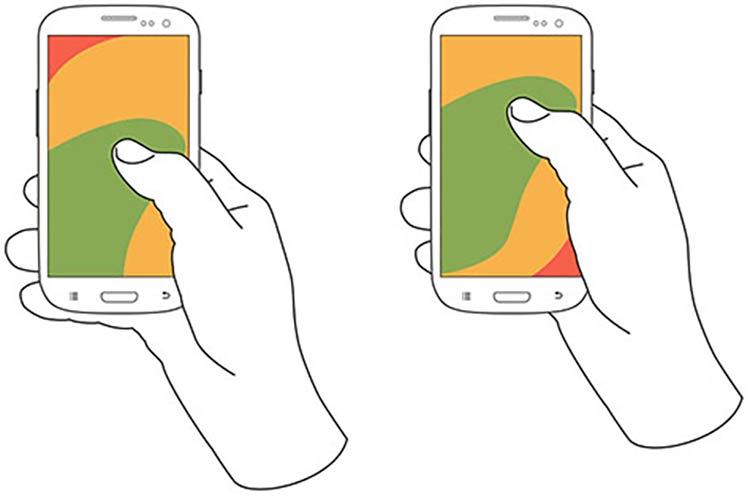

With this in mind:

- Limit the amount of text your users need to type.20

- Use large buttons and tappable areas so that people using small devices

can easily select them. Also be sure to include enough space around

them.11,17

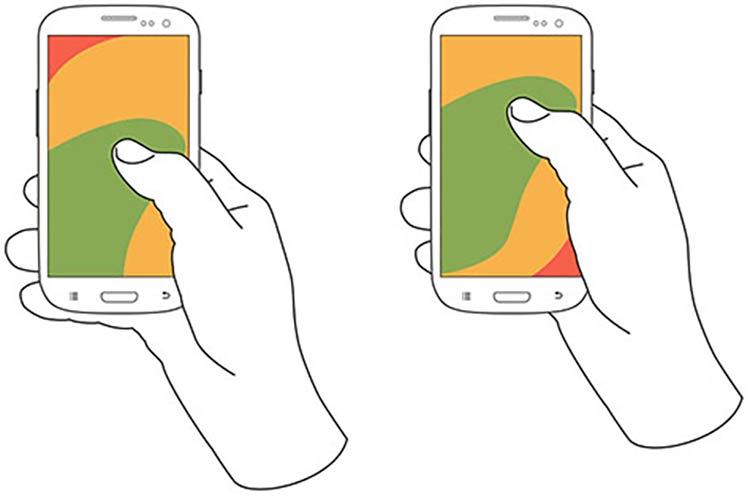

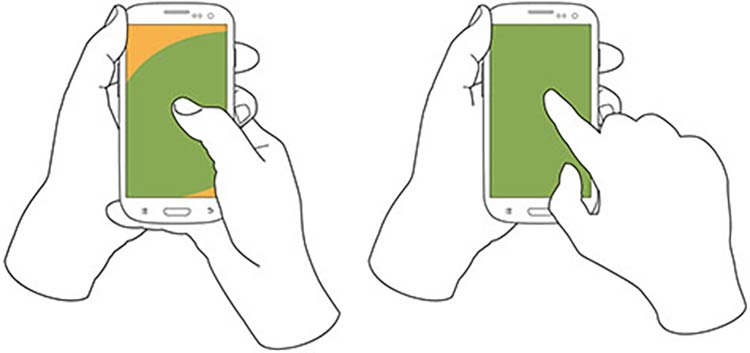

- Place frequently used buttons where they’re easy to reach. The easiest

places to reach depend on the size of the device and how the user is

holding it. In most cases, the center and bottom of the screen are

easier to reach than the top.17,79

Figure 3.15

Users hold their phones in various ways, but the center and

bottom of the screen are usually easiest to reach.

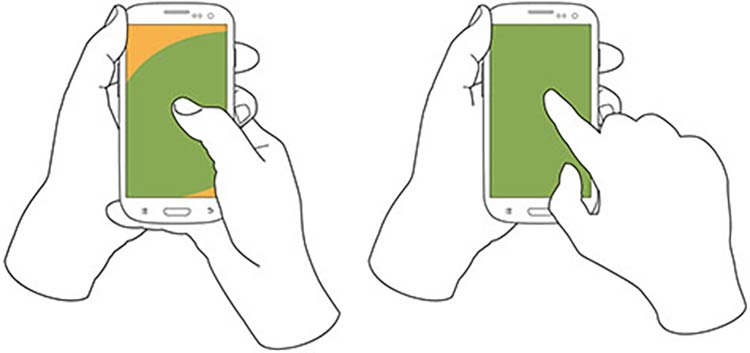

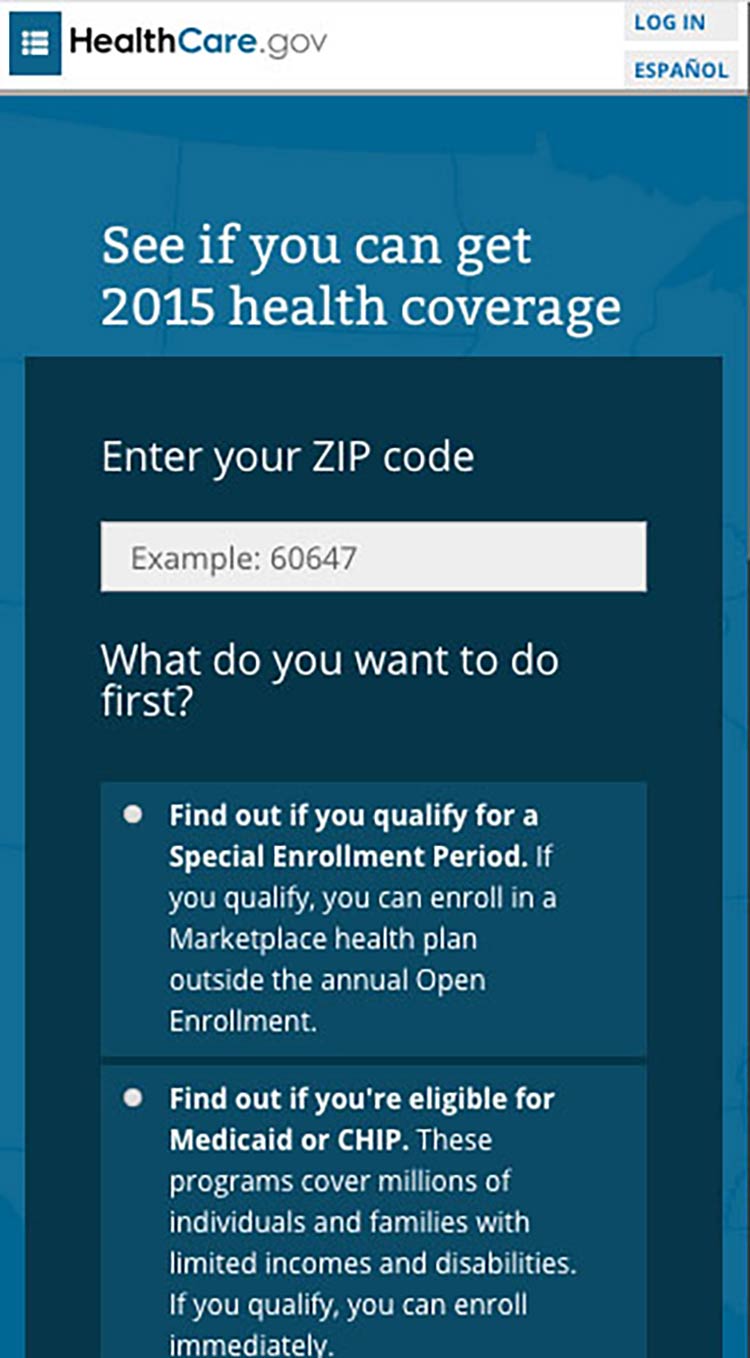

- Try radio buttons. Limited-literacy users find large radio buttons the

easiest way to make selections on a mobile device. Use them instead of

checkboxes or interactive icons.

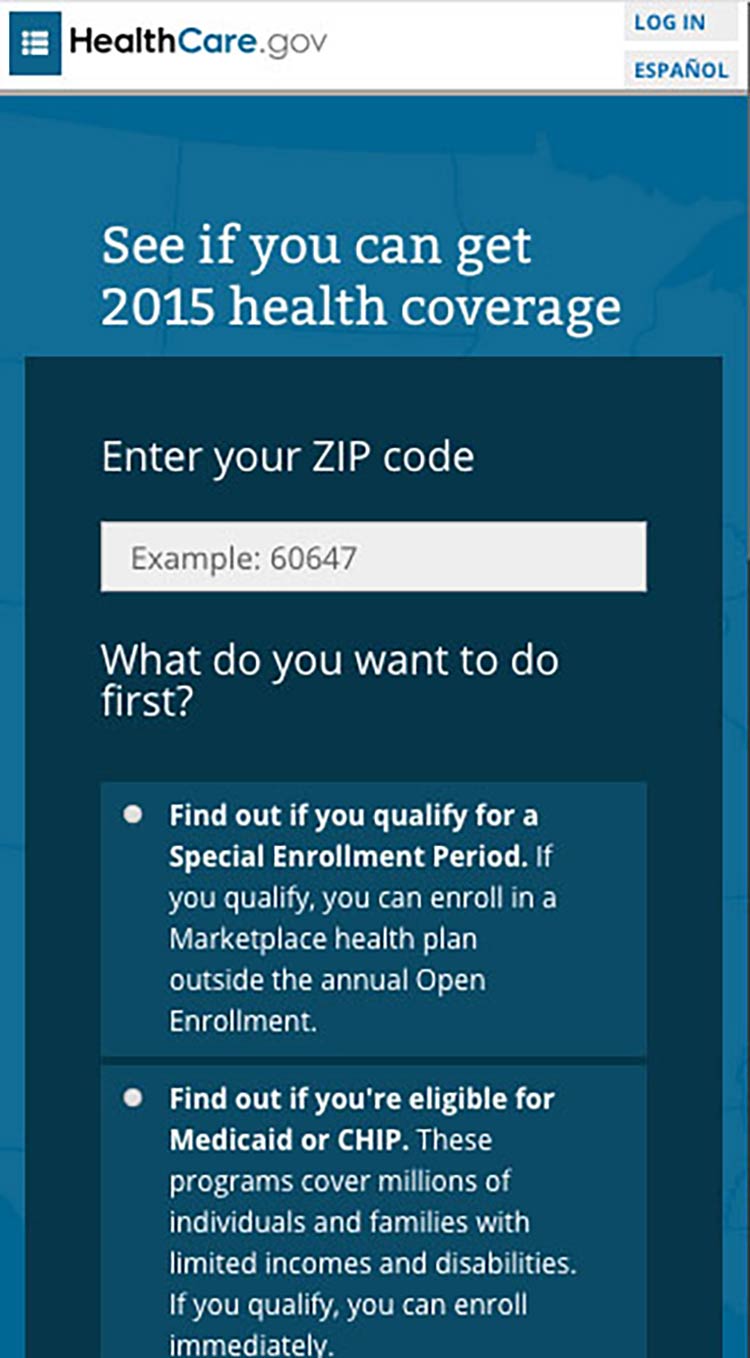

Figure 3.16

HealthCare.gov uses radio buttons for the answers to the

question, “What do you want to do first?”

Try this

To improve “tappability,” be sure the label is associated

with the radio button. That way, the label will be tappable, too—so

users have a bigger area to tap.

Summary

To be successful, web content doesn’t just need to be well written—it

needs

to look

easy to read. Thoughtful design and layout can help your readers focus

on your content without feeling overwhelmed, confused, or distracted by

how the information is presented.

Remember to think about all your users—including those on mobile and

those with accessibility needs—when you’re designing your site. Make

sure your content is accessible and easy to navigate, regardless of how

it’s accessed.

In the next section, we discuss content organization and navigation—that

is, making sure your users can easily get to the right page on your site

to find the information they’re looking

for.

4. Organize Content and Simplify Navigation

Introduction

This section discusses 2 important concepts related to the structure of

a website on devices of every size.

Content Organization (also called Information Architecture) is the

way information is categorized on a website. It typically involves a

category structure (taxonomy) and labels. Think about browsing through a

bookstore—clearly labeled sections (like Mystery, Nonfiction, and so

forth) help you find what you’re looking for. Good content organization

helps users find information quickly.

Navigation refers to how users move through the pages of your

website. Elements of navigation include menus, tabs, headers,

breadcrumbs, sitemaps, and “Back” or “Next” buttons.

It’s important to keep content organization and navigation simple and

consistent. Users are typically topic

focused.24,30 Organize and label your

content according to your users’ needs, and make sure you use terms that

are familiar to them.

4.1 Create a simple and engaging homepage.

Research tells us that web users with limited literacy skills have a

hard time processing more than 1 concept at a

time,7,34,50 so

make sure your homepage is a simple, focused entry point to the content

on your site. This is also valuable when designing for mobile—or even

better, responsive—websites.

Keep your homepage as simple as possible.

Limit the amount of text on the homepage.30

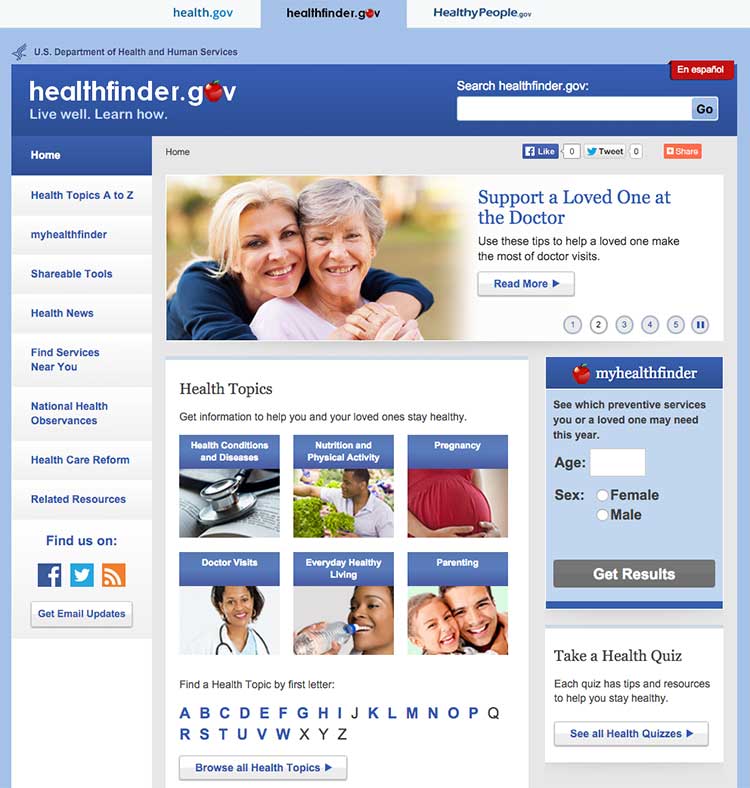

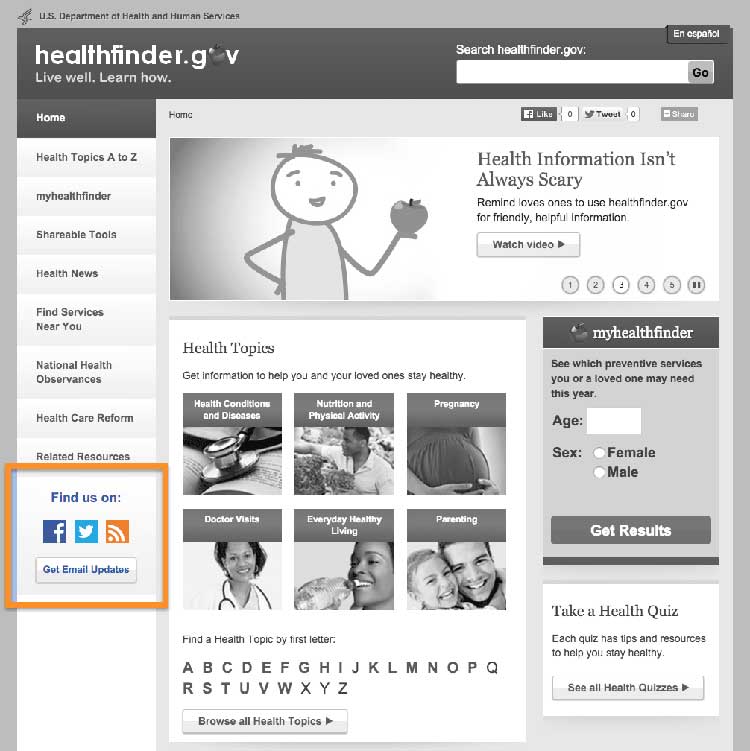

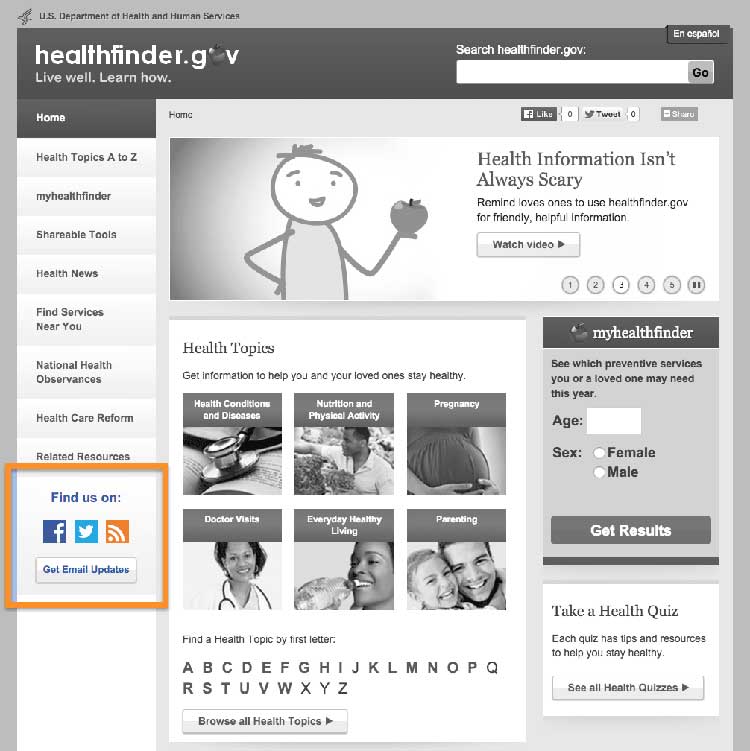

Figure 4.1

In usability testing, limited-literacy users were more

successful using healthfinder.gov’s mobile-optimized homepage because it

had fewer distractions than the desktop version.

A useful homepage is mostly links and short descriptions.24,30

Well-designed homepages include lots of white space and large buttons.

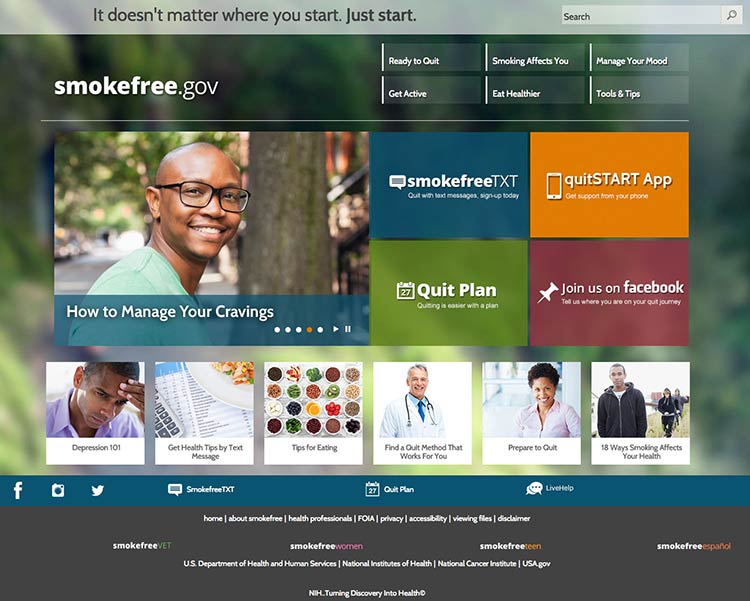

Figure 4.2

The smokefree.gov website is simple—it doesn’t have too much

text, it’s made up of mostly buttons to get users to more content, and

it has a large search feature.

If you include information in more than 1 language, link to the

non-English sections directly from the homepage. It’s also important to

link to non-English sections from a universal menu bar—that way, if

users find your content using a search engine, they’ll be able to find

additional non-English content.

4.2 Label and organize content with your users in mind.

Use words your users know instead of technical or “catchy” terms.24

Remember, your goal is to help users find what they need as quickly as

possible.

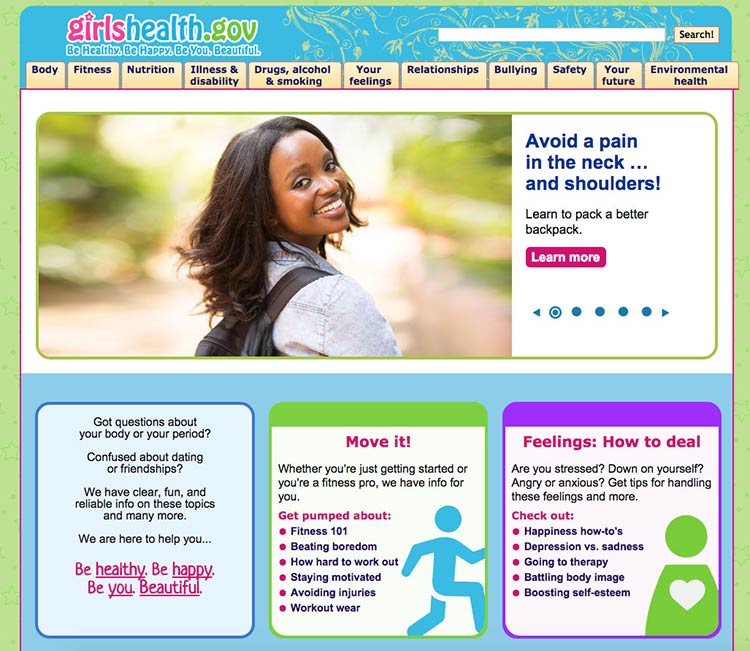

Figure 4.3

This page from the Office on Women’s Health includes a

navigation bar with audience-appropriate category labels (the site is

for girls ages 10 to 16). For example, the mental health section is

labeled “your feelings,” rather than a technical term.

People have different mental models (methods) for grouping health

information.36,40 To help different

users find what they need, repeat topics under multiple categories. For

example, based on card sorting, content on mammograms appears under 3

categories on healthfinder.gov: Cancer, Women, and Doctor Visits.

Try this

Next time you need to prioritize, rank, or organize types

of content on your site, try card sorting with your users.

Card sorting is a user-centered design technique used to organize

content intuitively. Start by creating an index card for each page of

your website. Then ask people to sort the cards into groups. This will

tell you how users expect to see content organized and labeled on your

site.

Alternately, you can have participants rank cards in order of importance

or interest. In card sorting exercises conducted by ODPHP, users with

limited literacy skills prioritized the following types of health

information as most useful:

- Basics I need to know (Understanding)

- I would like to learn more (Assessment)

- I can do this (Overcoming barriers)

- How will this help me? (Motivators)

- Ways I can take action (Strategies)

- Where can I go for help? (Community resources)

Learn more about card sorting on

usability.gov.

4.3 Create linear information paths.

Linear information paths can help web users with limited literacy skills

learn, understand, and move through content on your

website.8,28,38,80

Each topic or section of a site has its own linear path. This path

guides users through the section using a series of pages or screens. On

the first page, give the user a short overview of the content. On each

page in a section, include a button or link that takes users to the next

page. That way, users can move easily along the linear information

path.28,30,35,36,49,50

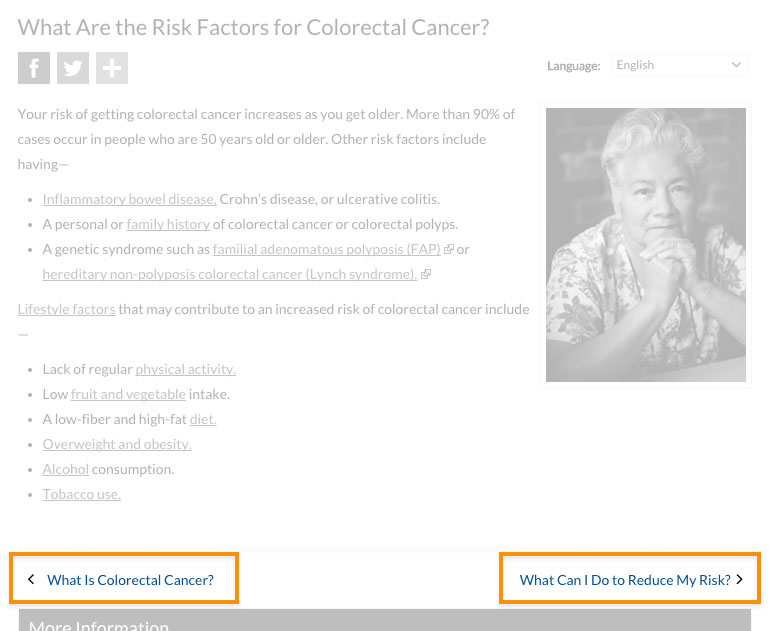

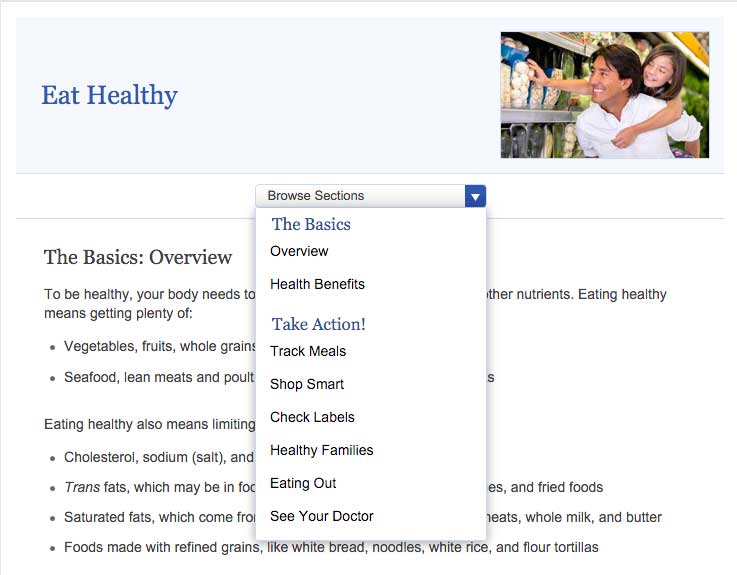

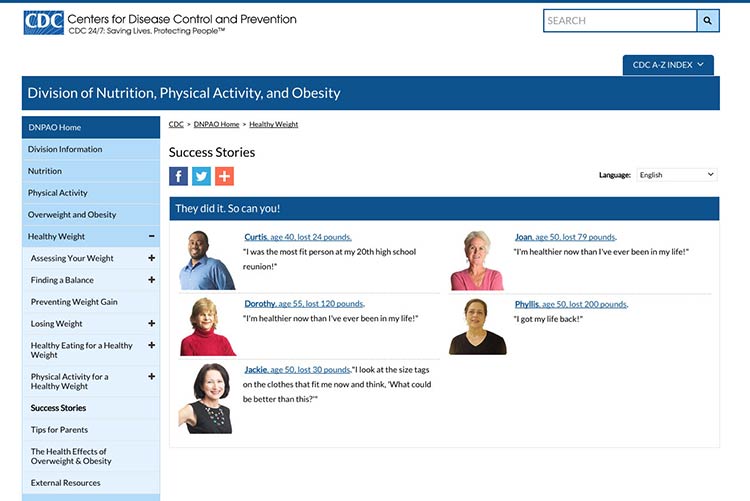

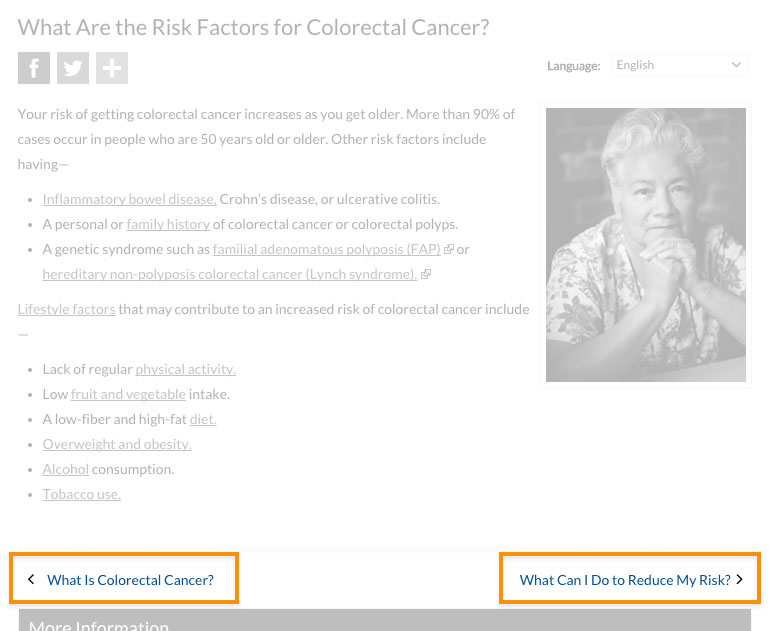

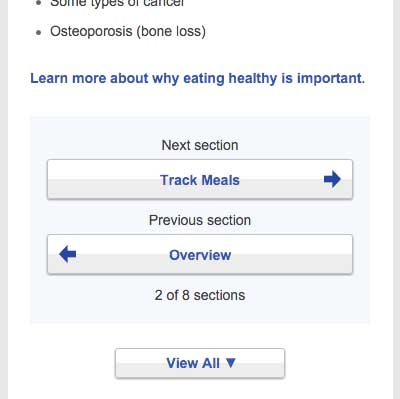

Figure 4.4

CDC uses links to help users navigate linearly through content.

If you can’t split content into logical chunks, keep it on a single

page.81 It’s better for web users to scroll than to

click through a series of pages without any clear logic.81 Be sure to

put the most important information at the top of the page.

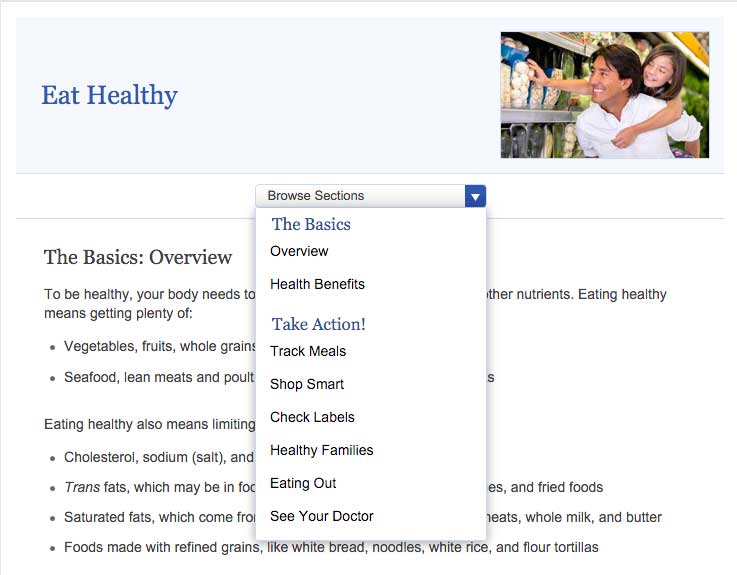

Figure 4.5

healthfinder.gov content is split into short, meaningful chunks

so that users can move through the content without getting overwhelmed.

4.4 Give buttons meaningful labels.

Include buttons or links with labels that tell users where they will go.

Web users will click through if you give them reason to believe the

click will lead them toward their goal.81

Skip page numbers or generic labels, like “Next” or “Back.”81 Instead,

use specific labels, like “What is cholesterol?” or “Back to the

homepage.”

Figure 4.6

In a study of healthfinder.gov mobile usability, users missed

the clickable page numbers. Instead of page numbers, healthfinder now

uses buttons with more meaningful labels.

4.5 Make clickable elements recognizable.

Users get frustrated when clickable elements—like buttons and links—are

difficult to spot.

Design buttons that are easy to find.

Make them:

- Large

- Bright

- A contrasting color from the surrounding text and background

- Obviously clickable30,35,36,50

Buttons that are obviously clickable have borders and shadows. If you’re

using a site design that doesn’t include borders and shadows, give

buttons a rectangular shape and rounded corners.66

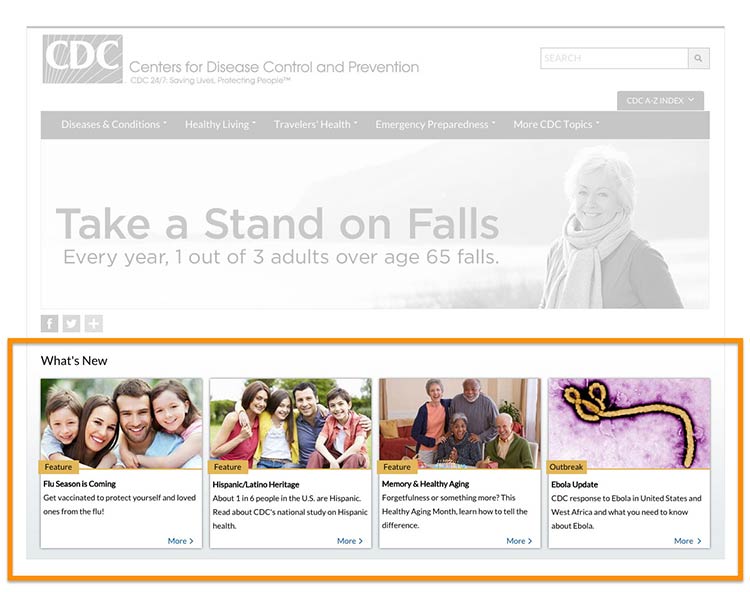

Figure 4.7

The buttons on CDC’s homepage look clickable because of their

shape.

Make button labels easy to understand.

Use a label such as “go” or “get started.” Some users with limited

literacy skills don’t understand the term “submit.”

Make buttons look distinct from other elements.

Users get confused when non-clickable elements look like buttons, so

avoid giving headings a background color or including lots of colorful

boxes on a page.66

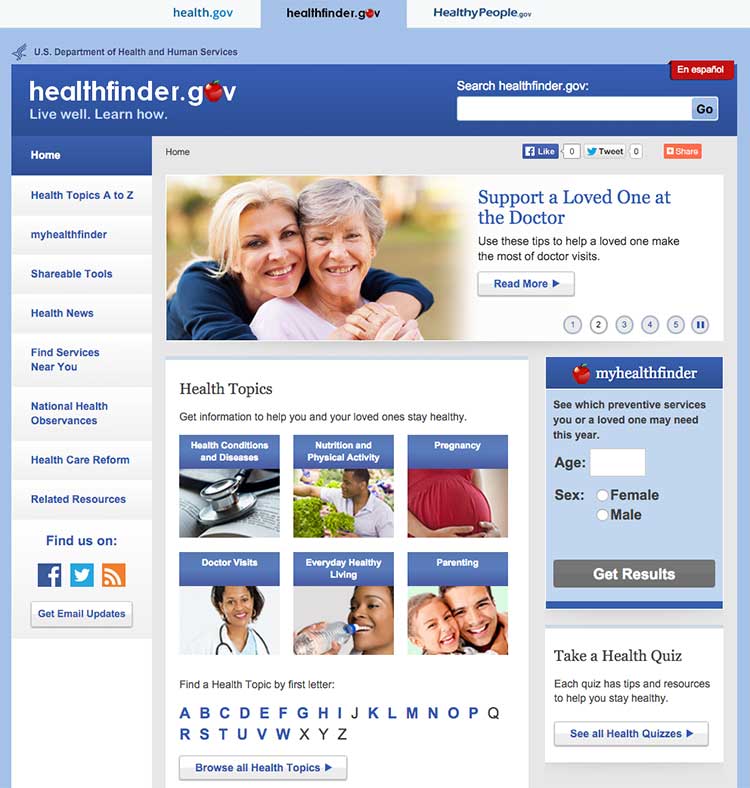

Figure 4.8

The myhealthfinder “Get Results” button clearly tells users to

click to start finding the preventive services they need. Clickable

buttons and icons have a unique style that’s distinct from other

elements on the page.

Apply clear visual cues to links.

Make it clear that links are clickable—avoid making users mouse over

text to see if it’s clickable. For example, make links blue or another

color that stands out from the body text.66 (See section 3 for more

information on making links look clickable.)

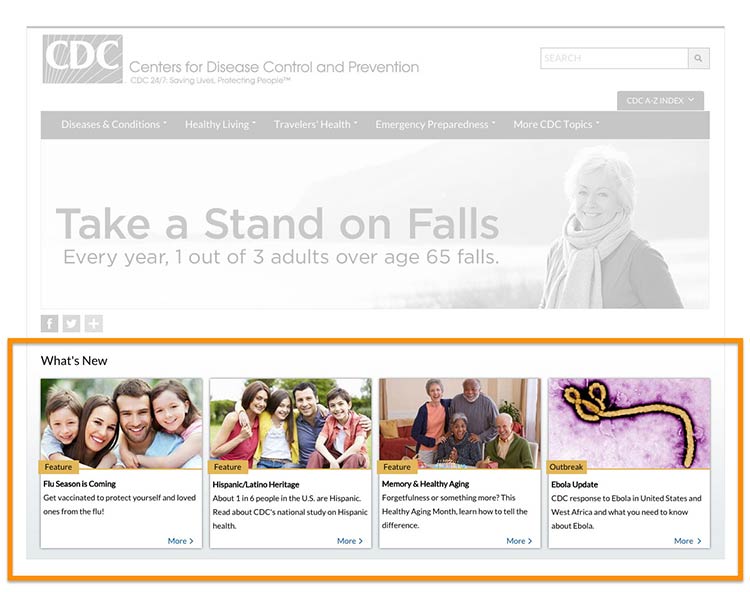

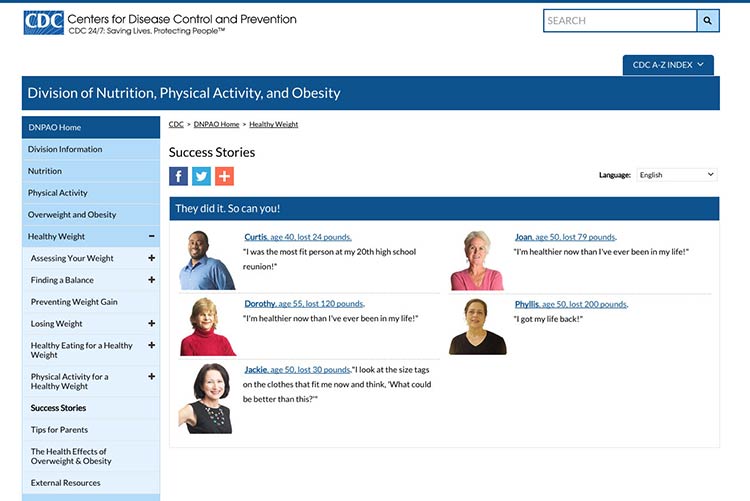

Figure 4.9

Links on CDC’s Healthy Weight Success Stories page are blue and

underlined, which sets them apart from the surrounding text.

Make all link elements clickable.

Make all elements—for example, a picture, icon, and text—that are

related to each other clickable. Users find it easier to click on a

large target area.66 If you’re using an icon for a link, combine it with

another visual cue, like a text label.66

Figure 4.10

Users can click the button, the icon, or anywhere in the box to

get answers to tax questions.

Be consistent.

Whatever button or link style you choose, apply it consistently across

your website.66

4.6 Make sure the browser “Back” button works.

Web users with limited literacy skills often depend on the “Back” button

to navigate a website,41 so it’s very important that

this button works predictably and consistently.

For example, when users enter data into a registration page or form,

make sure that the information isn’t deleted if users click the “Back”

button.

4.7 Provide easy access to home and menu pages.

Web users want the option to start over or jump between pages.11

However, we know that users with limited literacy skills typically don’t

use breadcrumbs.30,35 In ODPHP usability testing, users with limited

literacy skills were also unlikely to click on a logo in the site header

to get to the homepage.

With this in mind, include large buttons that take users back to the

homepage or the main menu pages on the site.30,35,39

Figure 4.11

NIH SeniorHealth uses a strong left-hand navigation menu. The

current section is highlighted with a different color in the navigation

bar so users can easily see where they are in the site.

Use a menu button for mobile.

Mobile devices have limited space. Instead of using a left-hand

navigation menu on mobile, add a menu button that opens a custom,

mobile-optimized menu. That way, users can expand the menu as needed.

Allow mobile users to go back to the homepage by including a home button

or a home option in the menu.

Users appreciate when they don't have to retrace their steps but can instead start fresh on the homepage.

Quote

Quote

“I like the “Home” button because it lets me correct mistakes

more easily.”11

Don’t rely on the “hamburger button” as a navigation cue—research

suggests that users don’t find it intuitive.81

Instead, try using the word “menu.”

4.8 Give users options to browse.

Many users with limited literacy skills will browse through categories

of content instead of using a search box.8,28,34,39 This may be because

they:

- Don’t see the search box (many users with limited web experience don’t

know where to look for a search box)

- Are worried about spelling mistakes

- Are overwhelmed by search results

- Don’t understand placeholder text in search boxes

Include multiple ways to browse for topics (for example, by topic

categories in an A to Z list).

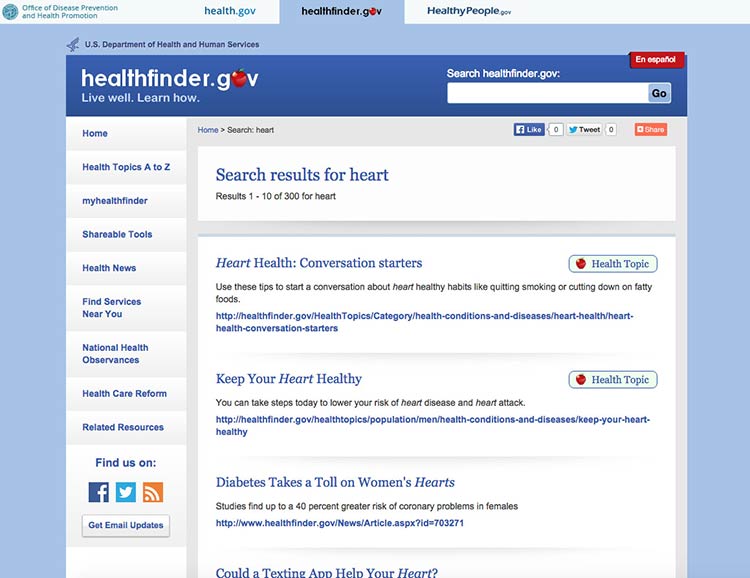

Figure 4.12

The healthfinder website allows users to search for health

information by topic categories, A to Z list, or search box, or by using

the left menu navigation.

4.9 Include a simple search function.

Web users with limited literacy skills are more likely to use a search

function that’s simple and user-friendly.

Make your search function easy to locate and use.

Use a large text box with obvious buttons.15

Use a “get started” or “go” button next to your search box.

During usability testing conducted by ODPHP, some users with limited

literacy skills clicked a “search” button without entering any terms in

the search box.49 A clearly labeled button will signal users that they need to enter a term(s) first.

Figure 4.13

The Healthy People website has a large search box and prompts

users to submit their search request with a “go” button.

Allow for common misspellings.8,30

Spelling is difficult for limited-literacy

users,3,10,15 so make sure your

search engine will still work if users make a spelling mistake. Help

users search by providing spelling and autocomplete

assistance.3,10,15

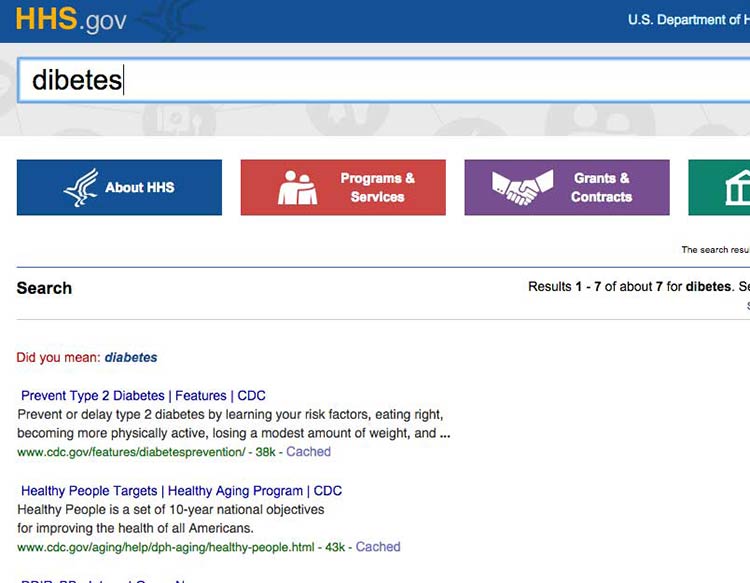

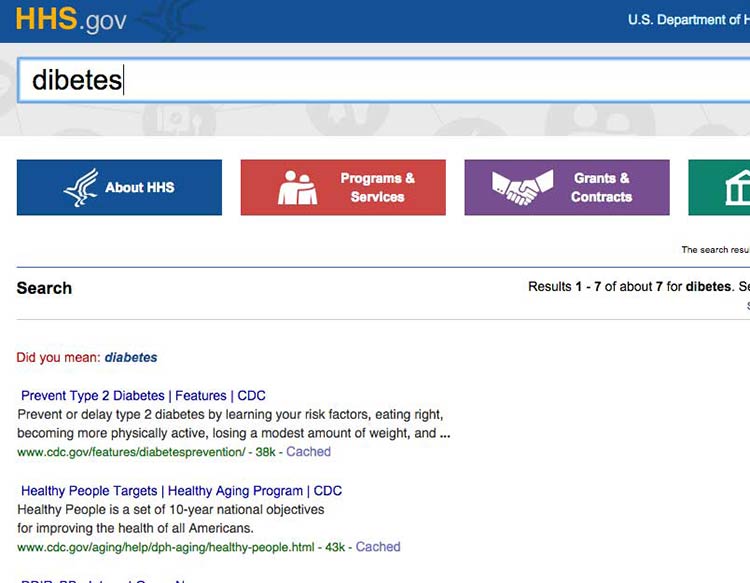

Figure 4.14

HHS.gov uses autocomplete to help users with spelling, and if a

search term is misspelled, the results recommend a word using “Did you

mean...”

4.10 Display search results clearly.

To streamline users’ search experience, display the most relevant

results first.15

Figure 4.15

The health.gov search function lists relevant health

topic results before related news results. Users usually find the most

helpful information in health topics.

When displaying search results:30

- Limit the number of results displayed on a page (unlike content-heavy

pages, use numbered pages to avoid scrolling)8,30

- Use clear page titles and include a brief plain language description of

each result8,15,30

- Avoid using long URLs if you can

- Use keywords in URLs when possible to help users scan

- Include lots of white space between results

- Use a large, easy-to-read font

- Highlight search terms in the results15

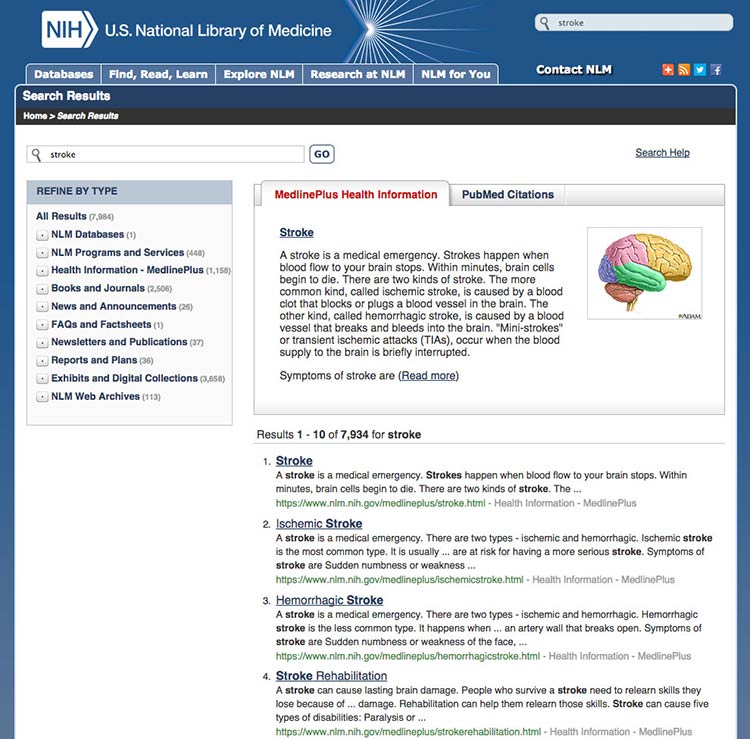

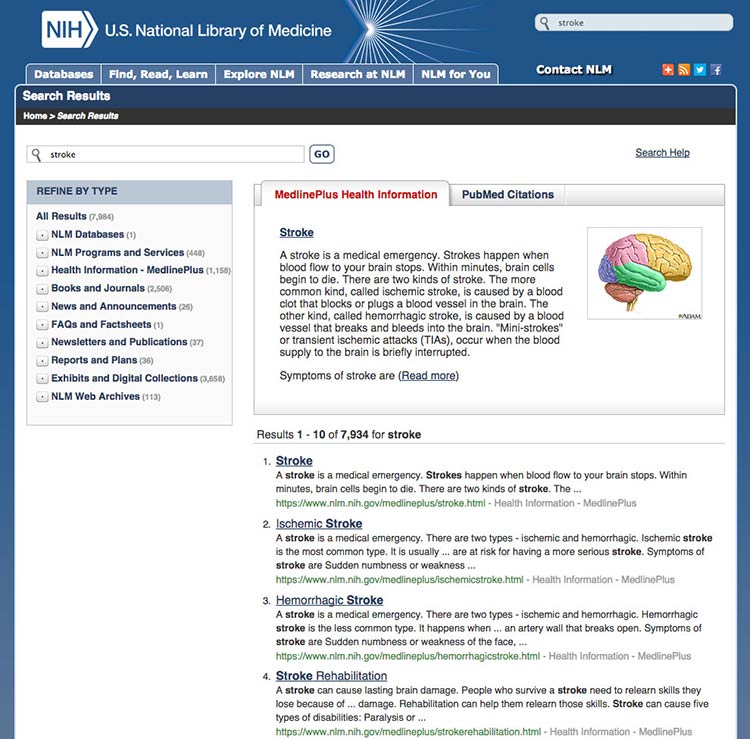

Figure 4.16

This search results webpage from MedlinePlus displays clear

titles and short URLs for the linked results. A brief description

written in plain language appears above the top results. Only 10 results

show per page.

Summary

Before users can read your web content, they need to find it. Construct

simple and consistent navigation that uses familiar terms, and organize

your content in a way that makes sense to your users. Give your users

options, like search- and topic-based browsing, so they can navigate

your site on any device in the way that’s easiest for them.

When your site is organized well, users can quickly and easily find the

information they’re looking for—and they’re less likely to get

frustrated and give up altogether.

In the next section, we discuss strategies for engaging your users with

multimedia and interactive content.

5. Engage Users

Introduction

Section 2 introduced the idea of user engagement. Engagement is the

process of involving users in health content in a way that motivates

them to take action.31

Using multimedia like video, audio, graphics, and

interactivity32,82,83

is an effective way to engage users. For example, you might offer users

the opportunity to:

- Watch video testimonials of people like them

- Customize graphics to reflect variables they care about

- Enter personal data such as age or weight to get tailored

information

Remember, formatting and layout can dramatically improve the user

experience. Make interacting with multimedia content easy for users by

designing user-friendly forms, quizzes, buttons, links, and mobile apps.

It’s also important to make it convenient for users to access and share

web content from anywhere. You can enable users to share content with

their online networks by adding social media buttons to your website.

5.1 Share information through multimedia.

Whenever possible, provide health information in multiple formats—for

example, audio, video, interactive graphics, quizzes, or slideshows.

Multimedia can improve both learning and engagement, particularly for

users with limited literacy skills.82,83

Choose media that support your content.

Before you decide on which formats to use, think about the information

you’re trying to communicate. Each type of media fosters learning in its

own way.

For example, consider:

- Visuals to show spatial information (like maps)

- Text to communicate information you want users to remember in the long

term

- Sound to convey information you want users to remember in the short

term82

Make sure each piece of media you use supports the text—using media only

as decoration will distract your users.83

Make media accessible.

When using audio or video, be sure to include a text alternative or

transcript, so the content is accessible to all

users.84,85,86

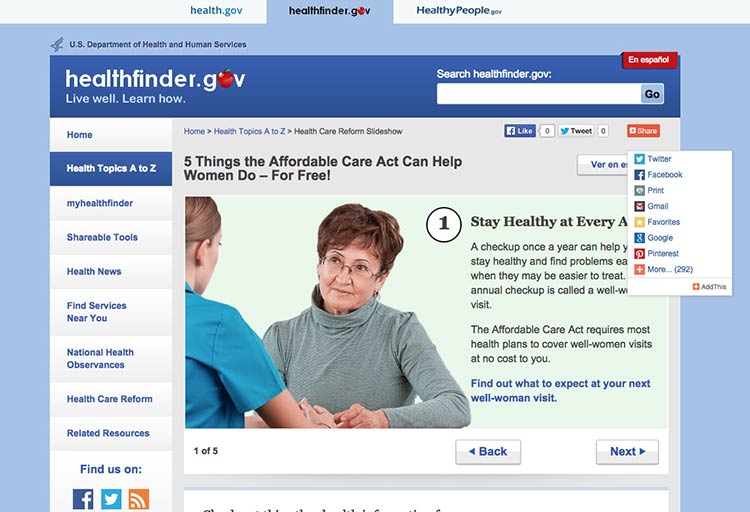

Figure 5.1

NIH SeniorHealth offers short video clips on popular health

topics. Each video includes a transcript and a help tool.

If you’re posting videos on a dedicated YouTube channel, use the closed

captioning options available. You can find details in these

instructions from

YouTube.

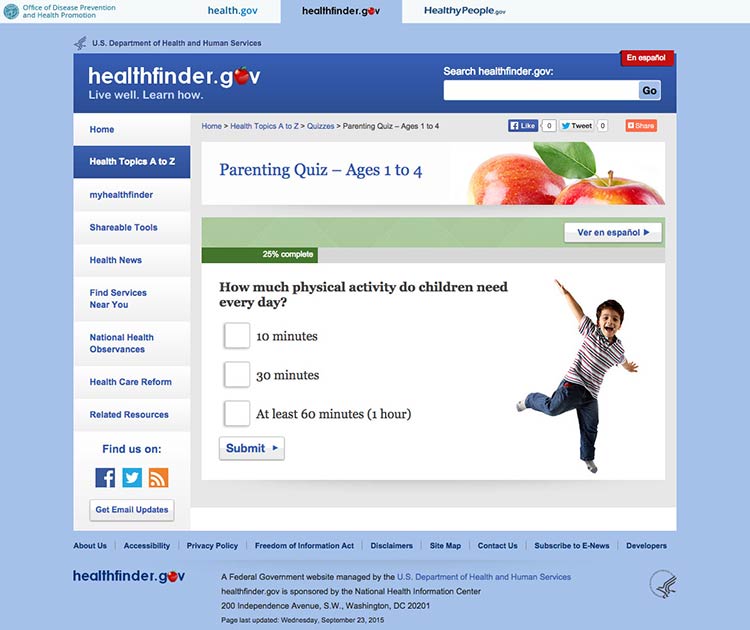

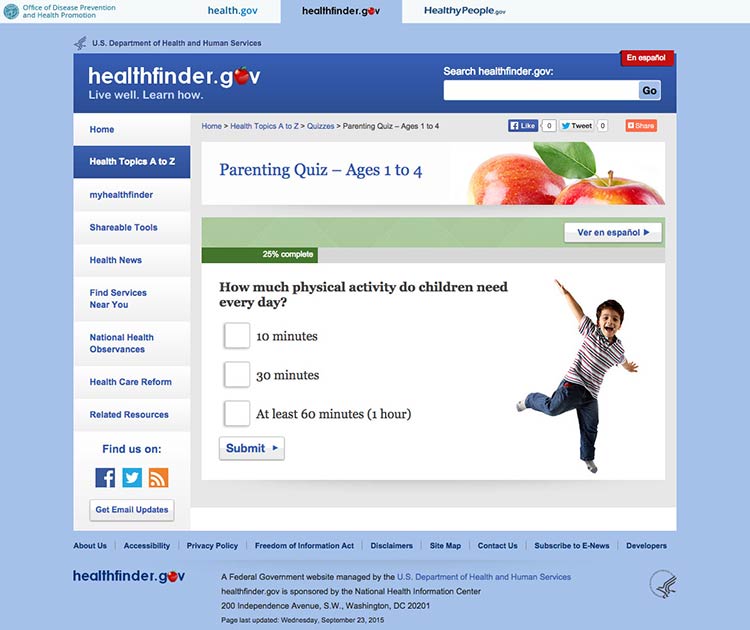

Consider quizzes.

Use quizzes to encourage active learning. Limited-literacy users like

quizzes and tend to complete them. After each question, give users

helpful feedback.82

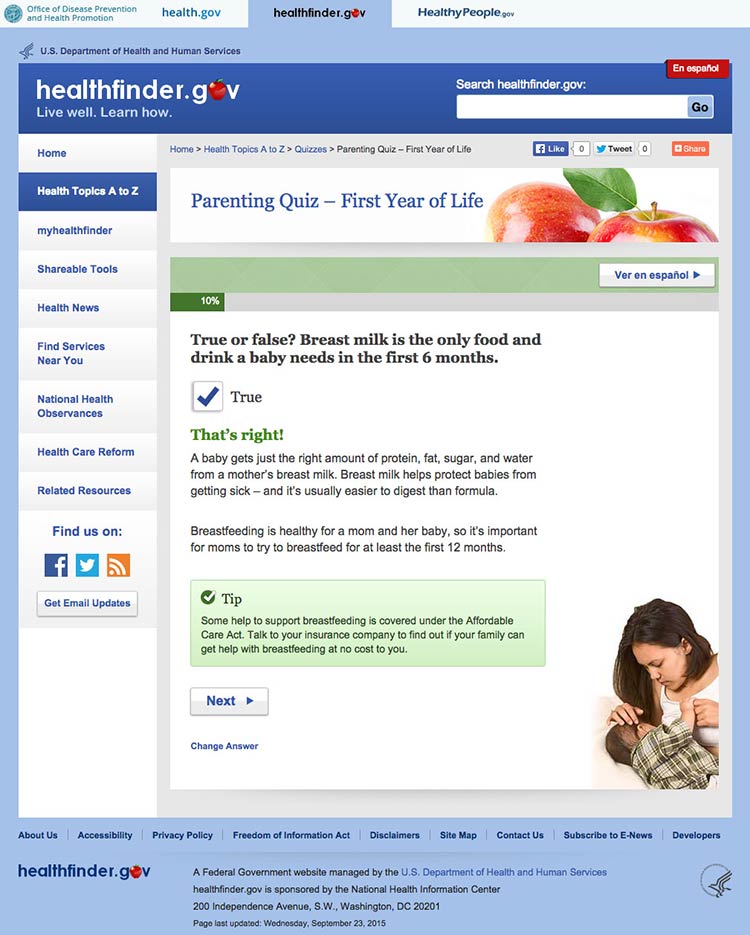

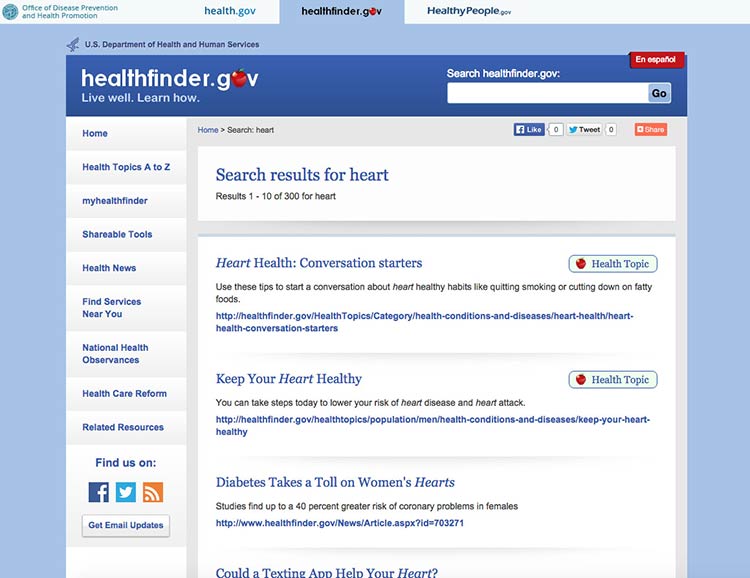

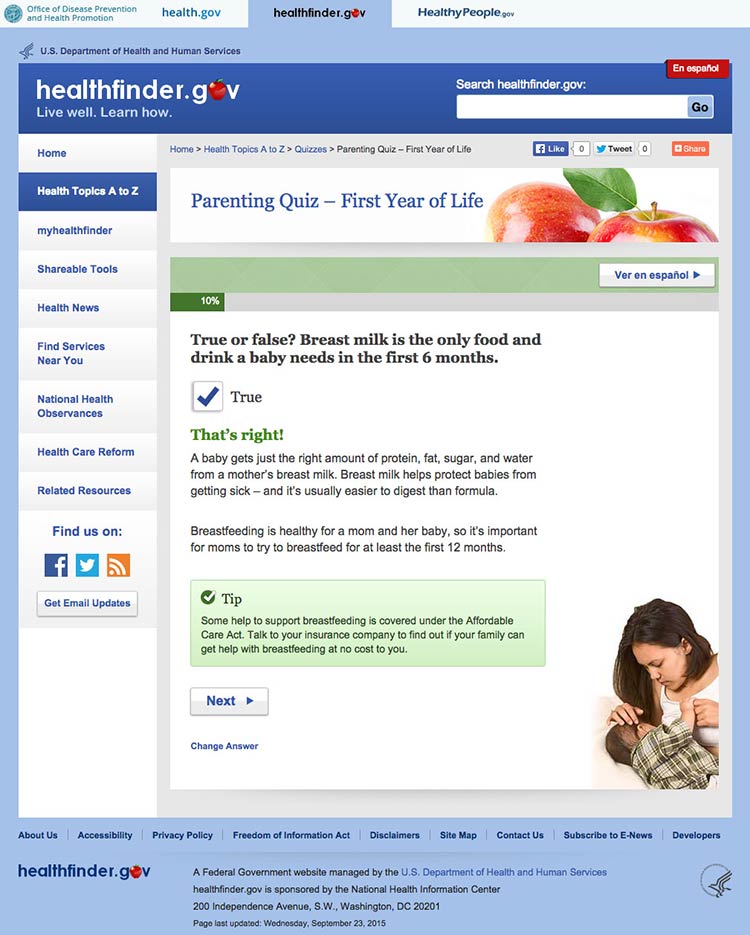

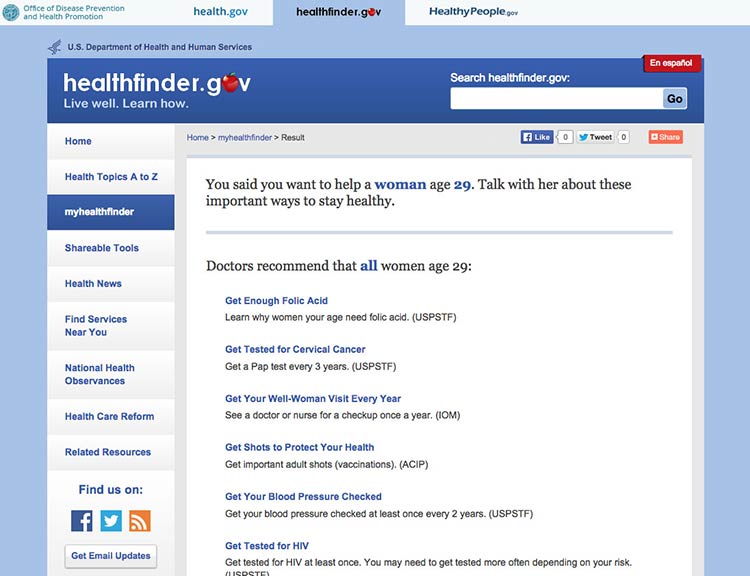

Figure 5.2

In healthfinder.gov usability testing, many participants with

limited literacy skills completed a parenting quiz on the website and

reported liking it. After answering each question, users get information

explaining why their response was right or wrong.

Try this

Look through your website’s content and ask yourself if

any of it can be repurposed as a quiz. Quizzes are especially popular

with limited-literacy users.

5.2 Design intuitive interactive graphics and tools.

Interactive graphics and tools allow users to make choices and see

results that reflect their choices.87 Many types of

graphics and tools—including decision aids, infographics, images,

charts, and maps—can be interactive.

Present choices one at a time.

Avoid asking users to make more than 1 choice at a time. This will help

keep users from getting overwhelmed.87

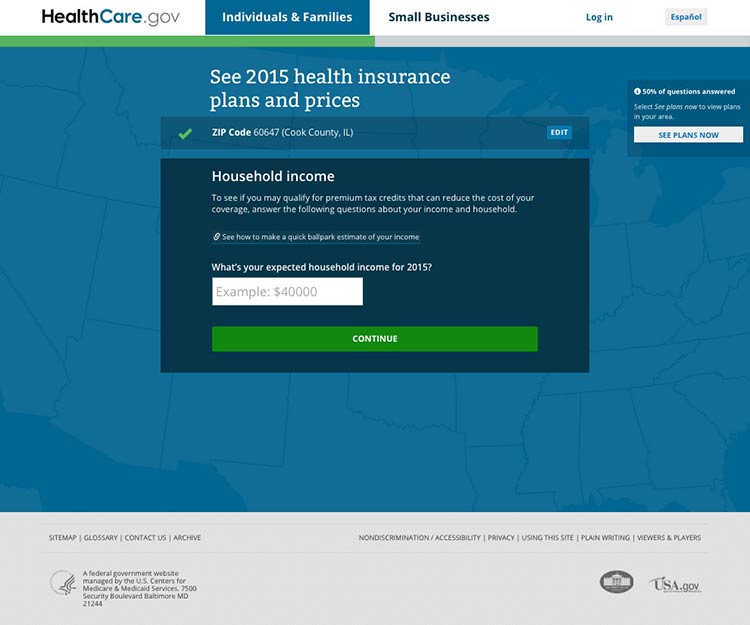

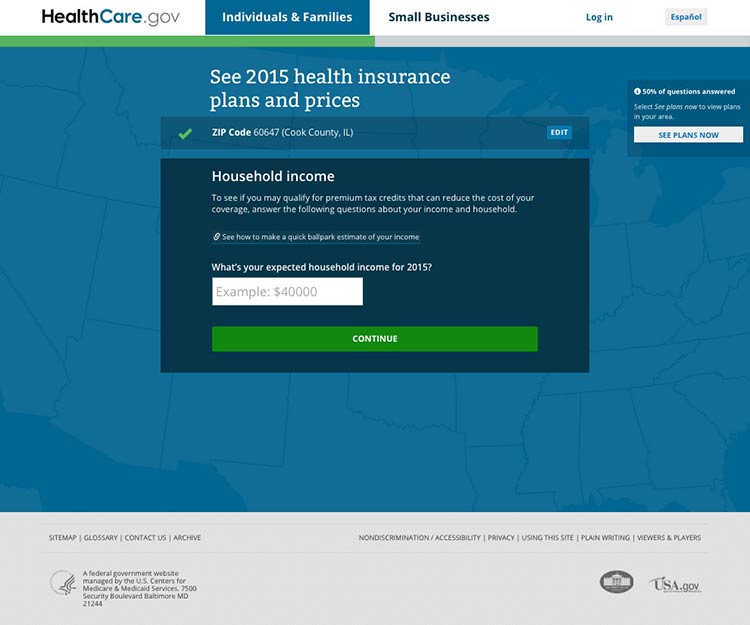

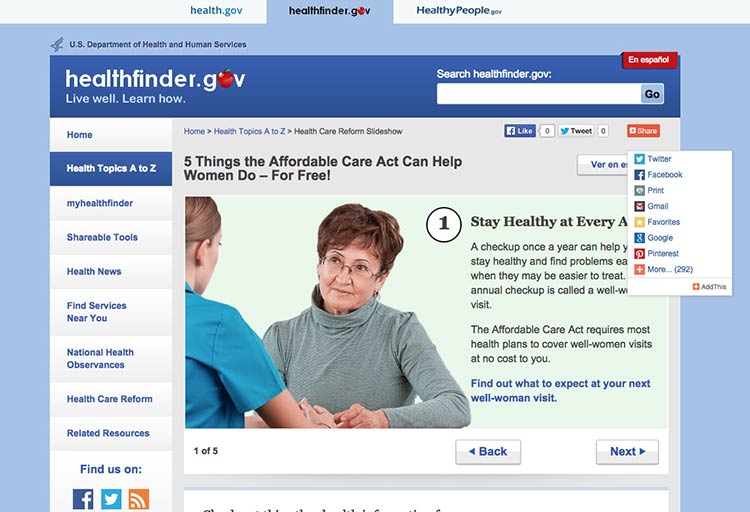

Figure 5.3

Healthcare.gov asks users questions 1 at a time before they can

see information about health care costs in their area.

Show that the graphic or tool has changed with visual

cues.88

If users can’t see changes, they’ll assume the graphic or tool isn’t

working.87 Use visual cues to indicate change—the more obvious, the

better.88

Include intuitive controls.

Users interact with a graphic or tool using controls. Include commonly

used controls that will be familiar to users—for example, radio buttons,

drop-down selections, and autocomplete fields.87

Make it easy to start over.

Allow users to easily clear their choices and start from the beginning.87

You may want to include a “Start Over” button for forms or tools that

have multiple pages.

5.3 Provide tailored information.

Invite your users to customize content to their personal interests or

characteristics. This will help encourage them to interact with your

content.

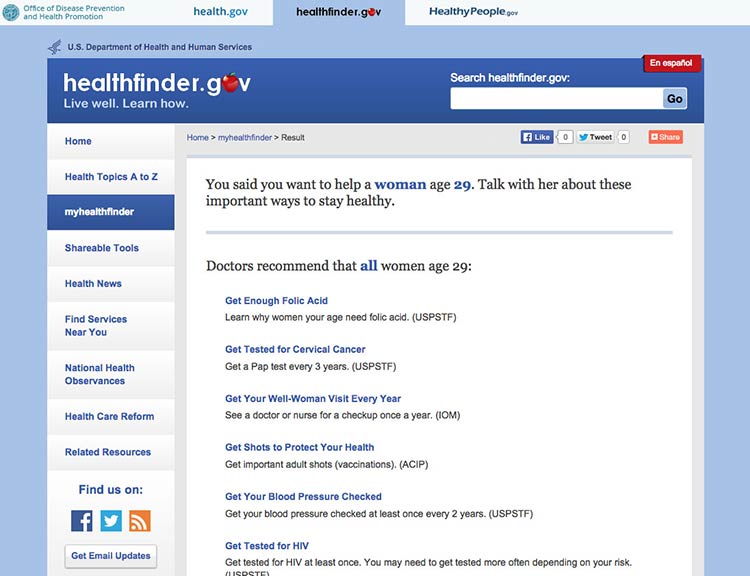

Figure 5.4

The myhealthfinder tool on healthfinder.gov prompts users to

enter their age, sex, and pregnancy status to get personalized

recommendations.

Avoid asking for too much information.

We know that users want personalized health information, but they don’t

want to enter a lot of personal

details.27,39,49

Consider interactive content that only requires users to enter a few

pieces of information about themselves.

Figure 5.5

To use the myhealthfinder tool, users only need to enter their

sex and age.

Create a link between the information you asked for and users’

personalized results.49

In other words, make sure users understand why you asked them to enter

a particular piece of information. This will help compensate for users’

limited working memory.

Quote

Quote

“I’m very comfortable [entering my age]. That way, I get exact

information for me, not different age groups.”

Figure 5.6

The myhealthfinder results page from healthfinder.gov includes

a summary of the user’s personal information entered on the previous

screen.

5.4 Create user-friendly forms and quizzes.

It’s important that forms and quizzes are intuitive and easy to use.

Make instructions clearly visible on the page.

Avoid asking users to click on a button or link to see the instructions

they need to fill in a form or complete a quiz.13

To follow limited-literacy users’ typical reading path, display fields

in a vertical

list23,89,90 and

put instructions above each field. If instructions appear at the

beginning of a section or to the right of a field, users may skip over

them.13

Figure 5.7

Users can easily follow instructions on the myhealthfinder

form.

Suggestion

The best-case scenario is that your quiz or form is so intuitive that it

doesn’t require many instructions in the first place.

Chunk information on forms into meaningful categories.

Grouping information in ways that make sense to users will help them

easily follow along.91

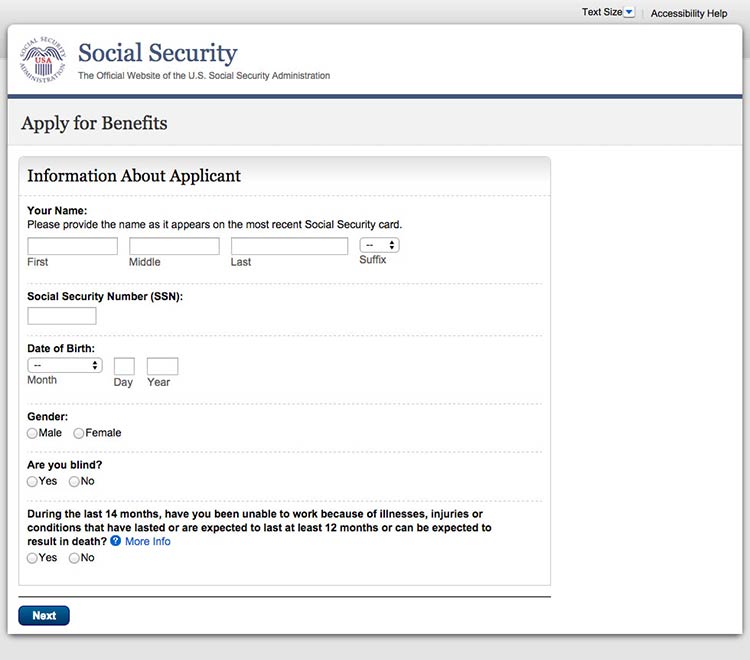

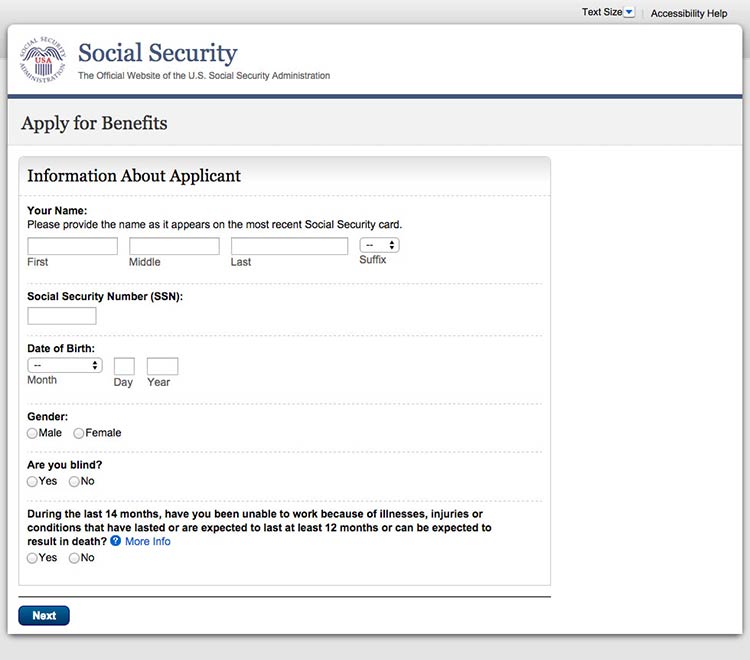

Figure 5.8

When applying for Medicare benefits, the form is chunked into

manageable pages like “Information About Applicant.”

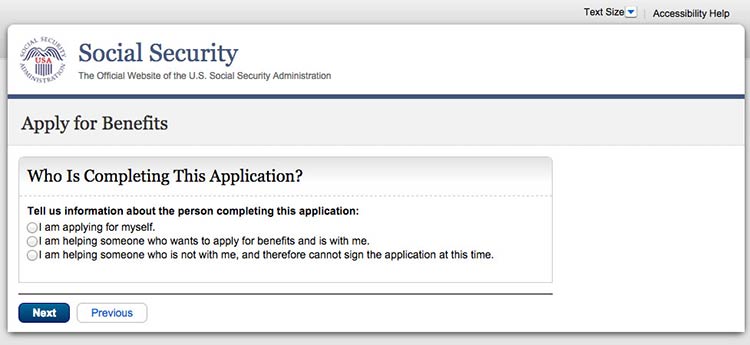

When designing a long form or quiz, use 1 of 2 layout options:13

- Show users 1 field at a time

- Allow users to scroll down to see all fields

Figure 5.9

This healthfinder.gov parenting quiz displays each question on

a new page.

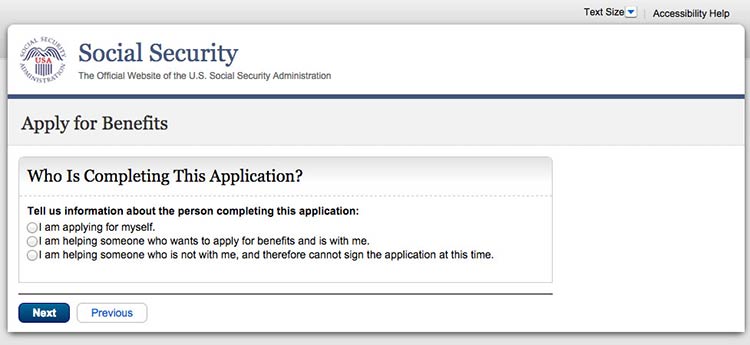

Figure 5.10

This initial page in the Social Security application asks users

for details about who they’re filling out the form for.

Keep required information on forms to a minimum.

The less information your users have to enter, the better. Also try to

avoid asking users to register. If you need to have a registration page,

ask for as little information as possible. Be sure to:

- Distinguish between logging in and registering

- Make the username an email address

- Keep registration to no more than 3 screens and provide cues (for

example, “Page 1 of 3”)

- Include a final results page with questions and responses

- Display fields that need corrections on a new page and include

instructions for correcting information23,89,90

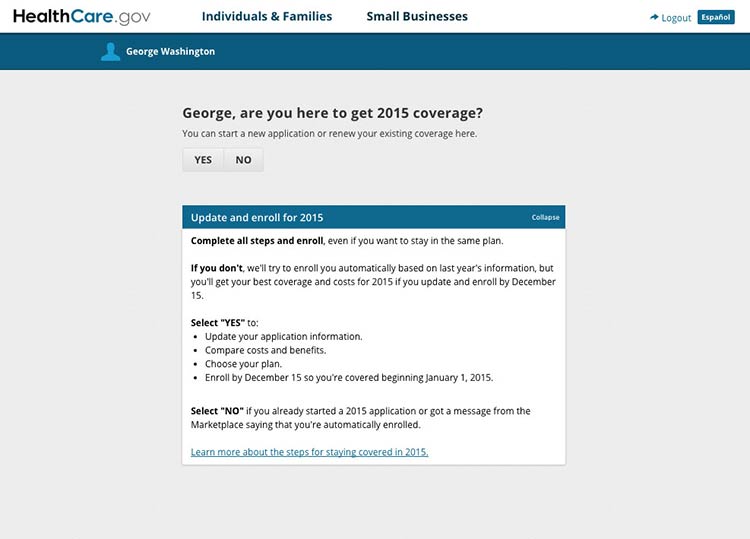

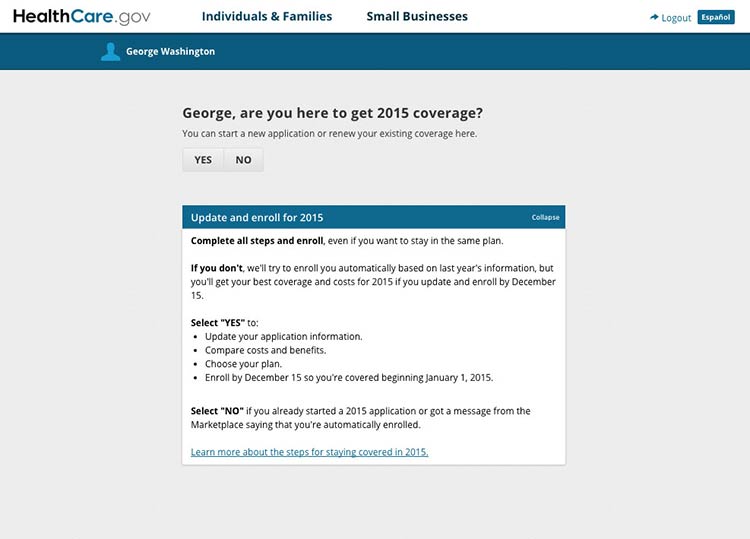

Figure 5.11

If a user is already logged in to Healthcare.gov, forms

auto-populate with his or her name.

Design forms for mobile.

Online forms can be especially challenging for mobile users when

important information or elements of the form run off-screen. Make sure