This content was part of the Healthy People 2020 Law and Health Policy project, which ended in 2020.

Using Law and Policy to Promote the Use of Oral Health Services in the United States

Good oral health is essential to overall health and well-being, but oral health problems are common. These common oral health problems like tooth decay, gum disease, and jaw disorders are preventable with regular oral care. But many people who need this care face barriers, which means they aren’t able to get the care they need.

This is a summary of the report, Oral Health: The Role of Law and Policy in Increasing the Use of Oral Health Services, which was the fifth in a series of reports that highlighted the practical application of law and policy to improve health across the nation. Each report also had success stories, or Bright Spots, that showed how communities used laws and policies to meet their health goals and achieve Healthy People Oral Health targets.

This report presented evidence-based and promising law and policy solutions that community and tribal leaders, government officials, public health professionals, health care providers, lawyers, and social service providers could use in their own communities. These solutions focused on improving oral health care financing, strengthening the oral health workforce, and removing barriers to using oral health care services. Many of these solutions aligned with the Heathy People objective to increase the number of people who use the oral health care system

Download Fact Sheet [PDF - 2.2 MB]

Key Finding: Financing and affordability often determine whether individuals use the oral health care system

- Medicaid is the most common form of public insurance, covering more than 86 million people each year.1 States must cover oral health services for children under age 21 who are eligible for Medicaid. The Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) program offers a comprehensive pathway to oral health treatment for low-income children and youth.2

- In addition to EPSDT, other government programs cover oral health care for eligible children. For example, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) provides health insurance for children under age 19 with family incomes that are too high for Medicaid. CHIP covers preventive, restorative, and emergency dental services.3 And the Indian Health Service (IHS) has developed successful oral health care programs for American Indian and Alaska Native children, who are more likely to have dental diseases than other groups.4

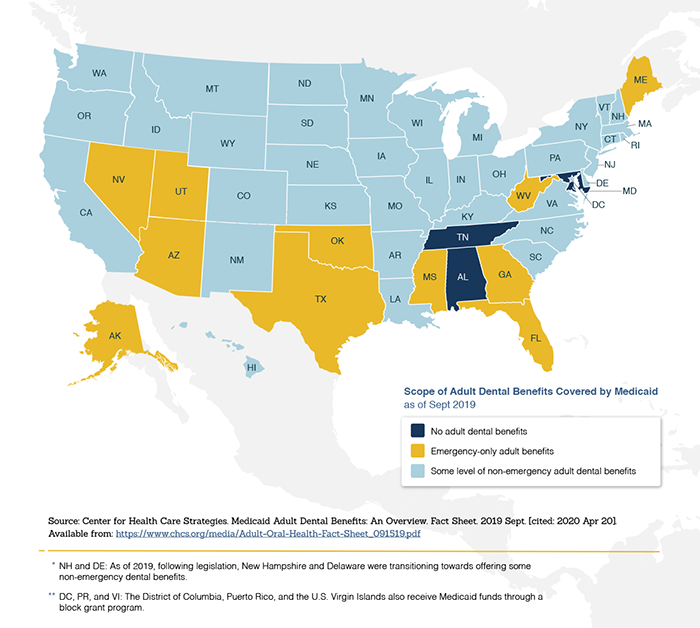

- Coverage for adults is more limited. As of 2019, 12 states only cover emergency dental services through Medicaid, while 34 states cover services beyond emergency care. Four states offer no dental benefits through Medicaid.5 Medicare also excludes most dental services for adults.

- In the past, only children, parents, pregnant women, people with disabilities, and older adults were eligible for Medicaid. But under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Affordable Care Act), states were able to expand Medicaid to adults with incomes below 133% of the federal poverty level (FPL). As a result, nearly 10 million adults gained dental benefits through Medicaid by 2017.6

- The Affordable Care Act also increased access to oral health care coverage by creating health insurance exchanges or Marketplaces where people could purchase insurance plans, including dental coverage. The Affordable Care Act also required plans to include dental benefits for children, but dental benefits aren’t required for adults.

- Federal programs can also increase access to dental services for specific populations. For example, the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (RWHAP) is a federal program that provides services for people with HIV, including oral health care. And the Office of Head Start (OHS), which provides services to prepare low-income children for school, ensures children are up-to-date on primary and preventive oral health services.

Graphic: Map of Scope of Adult Dental Benefits Covered by Medicaid as of Sept. 2019

Key Finding: Federal and state government play a major role in strengthening the oral health workforce

- In the United States, state governments have most of the responsibility for regulating the oral health workforce. States grant licenses to oral health care providers, define the scope of services for providers, decide on supervision practices, and create parameters for practice ownership, size, and configuration.7

- States can increase access by authorizing traditional and non-traditional providers to provide dental care. Traditional providers (dentists, dental hygienists, and dental assistants) can work alongside non-traditional providers (primary care physicians, pharmacists, community health workers, and social workers) to maintain a robust and comprehensive oral health care system.

- The federal government plays an important role in supporting health professions training for dentists, physicians, hygienists, and nurses. Federally supported programs can also improve access to care for specific populations.8 Federal programs and agencies like IHS employ dentists to provide care for underserved and vulnerable populations. Other programs like OHS and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) refer people to existing oral health providers.

- States can increase access to dental care through workforce-related legislation, regulation, and procedures. For example, states can expand the scope of services allowed for oral health providers, relax supervision requirements, expand teledentistry, and give more providers authority to write prescriptions. States can also encourage authorized dental providers to practice at federally qualified health centers to better reach low income individuals.

Key Finding: Many people face significant barriers to using oral health care services

- Even if people can afford care and have providers available in their area, they may face additional barriers that prevent them from getting the services they need. For example, many people don’t have reliable transportation to get to appointments on time, and many facilities don’t have convenient service hours. Many providers don’t provide services that are culturally and linguistically appropriate to their patients. And health information is often too complex for people to understand—particularly people with limited health literacy skills.

- Laws and policies can help reduce these barriers. Medicaid covers transportation to medical appointments, including oral health appointments.9 The National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and Health Care (CLAS Standards) offer guidelines for delivering culturally and linguistically appropriate services.10 And the Plain Writing Act of 2010 requires federal agencies to write communications in plain language.11

- However, only providers who receive federal funds are required to follow many of the laws and policies that reduce barriers to oral health care. Most oral health care providers work in private practices—meaning they don’t receive government funds and aren’t legally required to comply.

Graphic 1: States should ensure Medicaid recipients have transportation access

Graphic 3: States can implement national standards for culturally competent health care

Key Finding: Emerging trends impact the success of oral health interventions

- State and federal laws and policies can help meet Healthy People Oral Health objectives by reducing financial barriers to care—for example, by including dental benefits in federal and state programs or expanding eligibility for existing programs.

- Allowing new models of oral health care, including of the use of non- traditional providers, can increase access to care by underserved populations. Recent demographic trends like an increasingly aging population and widening income disparities suggest that government support for the oral health safety net will continue to be essential to ensuring access for those who don’t have private insurance.

- Addressing the social, behavioral, and environmental determinants of health as part of oral health care offers a new approach to prevention and treatment. These factors can inform new research and technology, which can lead to more personalized medicine and tailored recommendations to better meet the needs of high-risk individuals.

Key Finding: More research is needed to better understand the effectiveness of laws and policies that promote access to oral health care and reduce barriers to using services

- Health services and policy research can help ensure that payment systems and financing mechanisms respond to new ways of delivering care—and continue to make progress toward national oral health objectives.

- It’s important that researchers evaluate emerging models of care like state demonstration pilots for public programs or the emerging trend of “corporate dentistry”—when large practices with many providers are replacing solo practitioners—and their effect on access.

- Dental caries are the most common chronic infectious disease, and they disproportionately affect vulnerable populations. Although researchers have made progress in understanding how to prevent and treat caries, more research is needed to understand how best to prevent caries—including research on the value of providing dental equipment like fluoridated toothpaste and toothbrushes to low-income youth and the roles of saliva and bacteria in caries.12

- Researching effective messaging and strategies that increase understanding of basic health information can improve individuals’ decision making and help them better navigate the oral health care system.

Conclusion

The Healthy People 2020 objectives related to oral health are ambitious, but could have a considerable impact on health. To meet these targets, federal, tribal, state, and local communities and organizations will need to leverage existing laws and policies—and use data collection and research to inform future laws and policies.

To help the Nation meet objectives related to oral health, it’s important to:

- Increase the use of oral health care through laws and policies that decrease financial barriers to care

- Use state and federal laws and policies to strengthen and regulate the oral health workforce

- Improve patient experience and access by addressing barriers such as lack of transportation, limited cultural competence, and dental practice operating hours

- Develop or update policies that address emerging trends—like addressing the social, behavioral, and environmental determinants of health—for disease management in oral health care

- Conduct additional research to better understand laws and policies that will improve and increase use of the oral health care system

Taking these steps will help ensure that people live in communities where they can get the oral health care they need—ultimately leading to better oral health for all.

Related Healthy People 2020 Objectives

- OH-7: Increase the proportion of children, adolescents, and adults who used the oral health care system in the past year

- OH-8: Increase the proportion of low-income children and adolescents who received any preventive dental service during the past year

- OH-9: Increase the proportion of school-based health centers with an oral health component

- OH-10: Increase the proportion of local health departments and Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) that have an oral health program

- OH-11: Increase the proportion of patients who receive oral health services at Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) each year

1. Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. MACstats: Medicaid and CHIP data book [Internet]. Washington (DC): MACPAC. 2019 Dec [cited 2020 May 27] 155 p. Available from: https://www.macpac.gov/publication/macstats-medicaid-and-chip-data-book-2/.

2. 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396a(a)(10)(A), 1396a(a)(43), 1396d(a)(4)(B), 1936d(r), 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396o, and 1396o-1.

3. 42 U.S.C. § 1397cc(c).

4. Ricks TL, Phipps KR, Bruerd B. The Indian Health Service early childhood caries collaborative: a five-year summary. Pediatric Dentistry. 2015 May 15;37(3):275-80.

5. Center for Health Care Strategies. Medicaid Adult Dental Benefits: An Overview. Fact Sheet. 2019 Sept. [cited: 2020 Apr 20]. Available from: https://www.chcs.org/media/Adult-Oral-Health-Fact-Sheet_091519.pdf

6. American Dental Association, Health Policy Institute. Medicaid expansion and dental benefits coverage. Chicago: American Dental Association. [cited 2019 Oct 16}. Available from: https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/ HPIgraphic_1218_3.pdf?la=en.

7. Institute of Medicine (US) Board on Health Care Services. The U.S. oral health workforce in the coming decade: workshop summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2009. Chap 7, Challenges of the Current System. [cited 2019 Nov 22]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK219680/

8. Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant (Title V of the Social Security Act)

9. Social Security Act, §1902 (a)(4); 42 C.F.R. §431.53(a)

10. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health. National standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health and health care: compendium of state-sponsored national CLAS standards implementation activities. Rockville (MD): 2016. [cited 2019 Nov 25]. Available at: https://www.thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/assets/pdfs/CLASCompendium.pdf

11. Plain Writing Act of 2010, Pub. L. 111–274 (2010).

12. University of Louisville. Cavities are contagious, research shows. ScienceDaily 2014 Feb 20 [cited 2019 Nov 25]. Available from: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/02/140220112402.htm